50 Years of Statelessness: The Bengalis of Macchar Colony

This story first appeared in Voicepk.net

Half a century on – 50 years after West Pakistan lost its eastern counterpart – those who had taken the painstaking journey all the way to present-day Pakistan, travelling in a state of starvation and poverty, and hoping for better times to come – are living today in a country that has not even declared them its own. They live hopeless lives, scarred by frustration. Whatever little they earn is not enough to feed their families.

Aafia Khatoon, squints as she tries to remember what it was like when she arrived in Karachi. It was so long ago, the memory is like an old faded photograph. Her gray hair frames her face as it peeks out from under her dupatta, and a large nose-pin shines dully in the afternoon light. As she loses the battle in trying to rake her memory, she breaks into a pleasant grin, showing paan-stained teeth.

“I can’t remember much – I’m an old woman now!” she laughs speaking a dialect that is a mixture of the Noakhali and Cummila districts of Bangladesh.

Half a century on – 50 years after West Pakistan lost its eastern counterpart – those who had taken the painstaking journey all the way to present-day Pakistan, travelling in a state of starvation and poverty, and hoping for better times to come – are living today in a country that has not even declared them its own. They live hopeless lives, scarred by frustration. Whatever little they earn is not enough to feed their families.

Khatoon too came with her husband and three of her children, in the aftermath of 1971. Leaving behind her two married daughters in Bangladesh, Khatoon had three other children to take care of, and so she and her husband who wanted better economic prospects arrived in Karachi, settling in the locality now called Macchar Colony. The name is derived from the word machera (Sindhi) or fisherfolk and not ‘mosquito’ as many believe it to be, and this lack of understanding tends to further ostracize the locality in the eyes of many. And though she misses her daughters terribly, having no CNIC, Khatoon can never travel back to Bangladesh to see them again.

When she had arrived, the Pakistan Citizenship Act (PCA) 1951, was already in place, and particularly in Section 16A, it stated that those people who had been residing in present Pakistan’s territories before December 16, 1971, would be then officially declared as citizens of Pakistan. Their children born here would be considered citizens of Pakistan by virtue of their descent.

Today, NADRA’S (National Database and Registration Authority) own guidelines also recognize that a person is a Pakistani citizen if they can prove they have been residing in Pakistan since before 1978. In fact, this timeline provides an extension of seven years to the date that is mentioned in the PCA.

Yet even today, Khatoon has remains stateless – neither a Bangladeshi, nor a Pakistani. Neither country owns her.

“We tried to get a NIC made for ourselves. But there was so much red-tape involved, that we ultimately just gave up,” says Khatoon. “We knew nothing happen. Our lives would just remain the same.”

Without an ID card, Khatoon and her family have been limited to working at a shrimp peeling factory, which pays just a meagre sum of money: 700 Rupees a day.

Aafia Khatoon is not the only one. Other people who had arrived from Bangladesh in that time period are also facing the same ordeal. And with no documented identity of their own, those who belong to the ethnic Bengali communities continue to live miserable lives with little in store for them.

Muhammad Babul came to Karachi in the early 70s. He came alone back then but started his own family here. He lives in a house, whose main room on the lower floor is a shrine (aastaana) in remembrance of his father in law, a man whom he fondly calls Chacha. After Babul reached here, he was given refuge by ‘Chacha’.

“Chacha or father – it means the same thing to me. If it wasn’t for him I would not even be alive,” he says.

Sporting long locks, a henna-dyed orange beard, and several rings and bead necklaces, Babul looks after the ‘aastana’ which is simply decorated with tinsel and faded paper flags, while fairy lights adorn the walls. A large picture of his father in law is in front of the entrance, with a garland of flowers around it.

As he starts speaking, Babul’s anguish cannot be hidden anymore.

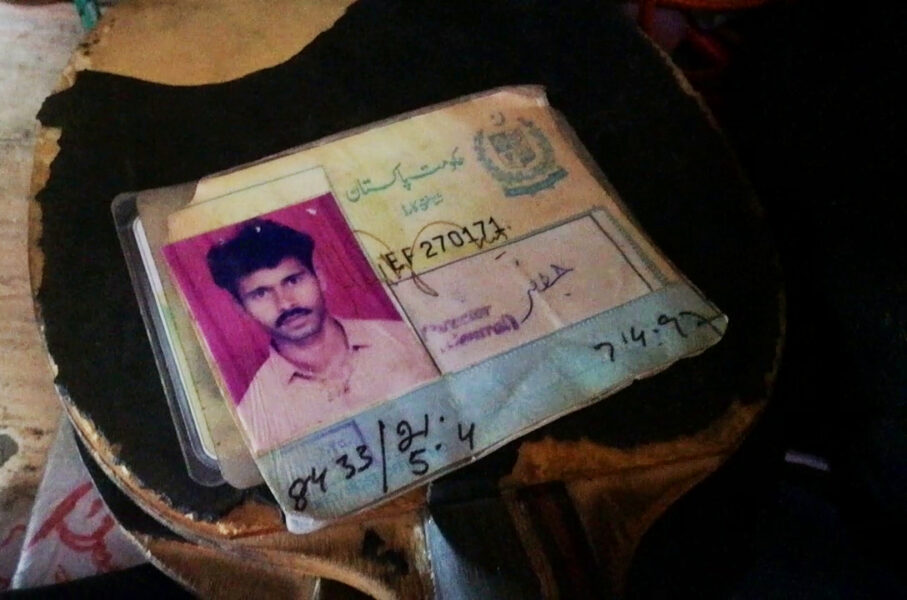

“I have been here since 1971, I even remember the day Ziaul Haq was killed in a crash,” says Babul. “I am as Pakistani as the rest of them, but to date I have never had an ID card.”

It is not like he did not try.

“I spent an entire year running to and fro. They made us run like mad just to apply for a card. I spent so much on transport, we did not even have enough money for food that year. But despite the time and money spent, I didn’t receive anything. All that happened, in the end, was that the NADRA officer told me they needed proof of my migration and my parents’ documents.

“I came when I was very little. My parents had died; from where do I get their papers?” he questions. “I am sick and tired of running around. In the end, I thought, first I should think of feeding my kids, then maybe God willing I will try again.”

There is almost no help that the community is getting from anyone else on the outside. But Imkaan Welfare Organization, founded by lawyer Tahera Hasan, has been making a huge impact in their lives. First and foremost they are providing legal aid by taking up cases of those whose criteria match the law, but they are still without CNICs. But the organization does not limit itself to this. In fact, the reason they began to research and work in the locality was that they wanted to study the children being brought up here. They set up a recreation centre, called Khel Ghar, just to start to get children off the streets, but it received so much popularity that it began growing organically, and young people still come there all day long to play table tennis, do gymnastics and to just spend their time. It is better than being out there with nothing to do, being exposed to dirt, sexual abuse, and drugs among other things.

Imkaan also provides medical services focusing on mother and child health as well as mental health services – around 100 clients who come for regular therapy – and awareness programs being given to both men (on domestic and gender-based violence) and women on marital conflict.

It was during their initial work here that Imkaan discovered the extent to which statelessness was prevalent.

“People who are stateless means they have no identity of their own, and no country is willing to recognize them,” explains Tahera Hasan. “There are multifold problems and challenges that occur because of this lack of identity: those who are affected cannot access public health, they cannot get into schools – educational institutions do not allow them to give matric exams without a B form; there is no permanent employment, so even when they work in factories, they work on minimum wages, and they don’t get any benefits. They also cannot have a SIM card issued in their name or buy property, or even get a drivers’ license.”

It does not stop there, either.

“Even during the lockdown, they had no access to COVID testing, and faced many challenges concerning vaccinations,” she adds. “Only now, a year later, has the government allowed undocumented people to be vaccinated. On top of everything they never got access to any relief packages, or Ehsas Programme – which were all linked to the identity cards.”

There are 126 Bengali communities in Karachi, and despite the fact that they are already marginalized and the poorest of the poor, they were still unable to access these rights and benefits.

MIGRATIONS AND THE FORMATION OF MACCHAR COLONY

According to Mohammad Jaffar, who arrived there when he was very little, Macchar Colony must have begun forming in the early 70s.

“A lot of people came here and settled: Pukhtoons, Afghanis, Punjabis, Sindhis but most of all Bengalis,” he says.

Statistics provided by Imkaan reveal that from a population of about 700,000 people dwelling in Macchar Colony, at least 65 per cent of them are ethnic Bengalis, and most of them work in the fisheries sector.

Two or three different types of immigration took place in Pakistan over time, which affected the demographics of Karachi specifically.

At first, it was the ethnic Bengalis who were already living in the then West Pakistan area prior to 1971, and who stayed on after Dhaka fell away. The migrations included those who arrived after this separation of East and West Pakistan. These migrations took place mostly from 1971 to 1978. There were also migrations from 1978 to 80, mostly due to economic reasons, and many of these people even returned to Bangladesh after their economic benefits decreased here and thought they would do better there. Tahera highlights that under the PCA, there is a birthright citizenship clause, where it specifies that all children who are born in Pakistan have the right to be given Pakistani citizenship.

In fact, the Bihari population living in Karachi – who are also subject to the same problems as Bengali communities – claim that they are true Pakistanis because they migrated from India to what was then East Pakistan, and then migrated again after 1971 to West Pakistan, and they should also not be deprived of nationality.

Mohammad Jaffar was just a child when he came here but he remembers a lot.

“Border control may not have been very strict here and so the West Pakistani authorities allowed several people to cross over – people who had been badly affected by poverty and famine, people who had lost their families in the war, or had to leave some of their loved ones behind. Entire families were broken up.”

But dynamics of power soon surfaced. Jaffar says those who came from the east, and established good relations with influential here, managed to make a stronger place for themselves. Others ended up being exploited.

“The local authorities have looted our people shamelessly,” he says. “Our community was hard working, they worked at sea, but later police officials would extort chunks of their daily wages, or create situations where bribery was the only way out. This has been happening for decades. Political parties have come and gone yet not one of them in power have thought of providing us with our basic rights of electricity, water or gas.

WOMEN AND CHILDREN

Like any other downtrodden area where economic issues are rampant, in Macchar Colony, women often get the raw end of the deal. Intersectionality reveals that while men are struggling, women suffer more, sometimes in the form of gender based or domestic violence.

Babul’s niece through marriage, Rozina says men have the freedom to marry or to leave whenever they want and this is what she has seen in her life. Her father divorced her mother when she was three years old, and when she turned eight, he left for Bangladesh without a thought for his child.

When she got married at 18, her husband and in laws kept pressurizing her to bring in more dowry, but eventually ended the marriage in a divorce, leaving Rozina to care for her son alone.

“Initially my father in law wanted to marry my mother but upon her refusal he made his son marry me. I think their intention was to take over our house,” she says.

Now 21 years old, Rozina lives with her mother upstairs in the same house as Babul, and does some work when she can. Mainly it is her mother who works for the fishery but the wages are few compared to their needs.

Because her mother has always been the only bread earner in the family, Rozina missed out on her studies, a fate which several children, but especially girls have to face here. She has been working since she was 15 and bit by bit they changed their shanty hut into a concretized home.

“Eighty per cent of the women living in Macchar Colony go out for work,” says Rozina. “They go to the fish factory and work there. Some women work inside their homes but this kind of work doesn’t pay much – I have to work inside the house too because I have young children to take care of here. We get around Rs800 to 900 a day that’s it for work that’s about eight to 12 hours long, maybe even longer.”

Babul’s own wife has to work for long hours – sometimes even 15 hours and they all must work while standing. The work comprises packing or sifting, and the women who stand for so long end up with serious health complications – with legs and feet affected as well as back problems and since they work in cold temperatures they suffer those as well. There are transport issues as well, as they have to come back home so late at night. They hardly get enough rest though because they must wake up again at dawn, cook food and then leave by 7 am for work again.

“How do we get out of this poverty? This is our life, we have accepted it,” says Rozina smiling sadly. “Still I will try and educate my son as much as I can.”

CNIC WOES

For Rozina having an ID card made is difficult because the information on her mother’s card is not correct. “When my mother had her ID card made she asked someone else to do the paperwork because she could not spare any time off from work,” says Rozina.

Some of these slippery dealers have even gone so far as to take around Rs100,000 in order to have ID cards made for those who need them desperately – mostly for work purposes. But many of them disappear soon after getting the money.

“An old man in our extended family is very worried because if he doesn’t get his ID card made, his whole family will suffer. But he has been conned a few times, by people who take his money and run, which is sad really. He really wishes to go for Hajj or Umra but he cannot.”

GOVERNMENT FAILURE

Tahera Hasan says that if PCA is fully implemented, then 80 per cent of the problems these ethnic communities face will be resolved.

“Then it comes to the remaining 20 per cent who have absolutely no documentation at all,” she says. “For them, the government can start Alien Registration or something else, but even in their case, their children who have been born on Pakistani soil, have a right to Pakistani citizenship.”

The biggest failure of the government is the non-implementation of law. Along with that the prejudice within the frontline workers in government institutions, resulting in the process being stalled for long periods of time. The moment such people see that the applicant is a Bengali or a Bihari, there are other types of challenges that happen.

Tahera says initially it was NARA (National Alien Registration Authority) that gave Bengali citizens their cards but even under that there was some discrimination. Several people even ended up with their citizenship being cancelled for vague reasons.

“Sometimes clients do exaggerate but there definitely is some ethnic discrimination against them,” she says. “There has been departmental corruption in that regard so we gave them door to door awareness on the issue. But there is so much lack of education on the matter.”

Now that NARA has been wrapped up and NADRA deals with everything, such an applicant’s information is sent to the DC for approval, but in many cases, it is also sent to the International Bureau for checking. In this whole system, anyone can reject citizenship.

It brings to light the level of prejudice that is actually deep-rooted within Pakistani society against ethnic Bengalis. Jaffar believes that there is so much of it, and so systematic, it almost seems as if society wants them to lag behind so that they are easier to exploit.

“First of all if the father has a CNIC, the son can have his made; if the father doesn’t have one, the son won’t either,” he says. “Some people left their ID cards behind in Bangladesh, some brought them. If a NADRA officer who is prejudiced knows the applicant is a Bengali, he will say something like, “This is impossible to get made”. After this the applicant is ready to pay a bribe for this important piece of evidence. What can a poor person do? You need ID cards even to go to the sea to catch fish.”

Jaffar’s uncle brought him and his sister to Pakistan after their parents died.

“Now when NADRA asks me for my father’s documents, where do I get them from?” he asks. “They insist that I bring a blood relative. The only blood relative is my sister who is so old that she cannot even walk to the bathroom by herself. Everyone else is dead now. But I was born during the war, and when they treat a person like me this way, it hurts because I have lived here all my life. I could die for this country but they will still not accept me.”

Jaffar says the way Bengalis are treated, is worse than a stepchild is.

“We are looked upon as slaves. They think we are the scum of the earth. And though this prejudice targets all ethnic communities, Bengalis face a hard time dealing with it.”

Jaffer is the proud father of a young girl who is an award-winning gymnast, and while he wants to accompany her everywhere when she is on tour, he cannot go because he has no card.

But Tahera says, “It’s not like there is a departmental policy to discriminate against this part of the population, however, there is an attitude of discrimination and a filtered down process against these communities which breeds prejudice,” says Hasan. “Things have greatly improved after NADRA began a crackdown here and closed down a few of these businesses.”

In a situation where ethnicity matters so much, to protect their children from being labelled, parents have even begun teaching them Urdu instead of Bengali. In many Bengali households, even though the parents know how to speak in Bengali, the children cannot.

“We have to clear them of this identity,” says Rozina. “The police causes problems for us Bengalis.” On the other hand like Aafia Khatoon, many of the older generations don’t know any Urdu, even though they have lived here all their lives.

A DARK FUTURE

Meanwhile, in one of the largest garbage dumps life goes on uninterrupted.

Everywhere around there is litter, cacophony and the ugly odour of fish hanging in the air – but for some it is paradise. A boy is completely passed out, and leans against the scum ridden wall his mouth sagging open; he is ignored by the others who huddle busily like flies over their precious purchase, squatting in knee-deep waste.

One must be daring enough to enter this muck, yet these addicts are in a state of euphoria. A couple of the boys, turn around slowly and robotically to see who is watching them – their eyes are glazed but completely cognizant of what is happening.

This is a common enough sight in Macchar Colony on a daily basis. Children as young as 13 can be seen converging in dark corners lighting cigarettes and sharing joints. They are society’s rejects, but these are the only places that will welcome them with open arms. In the whole of Macchar Colony, there is not one playground to be seen. Any empty space is filled with garbage. Houses are scrunched up next to each other. From ship breaking to fish factories, this area thrives on pure functionality: all work and no play.

Jaffar remembers a time when Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra – himself a Bengali – inaugurated a school here. But the other governments of the province and city have been so inattentive that generations have been ruined.

“This entire zone has become a huge hub for drug peddling,” he says. “Everyone is selling heroin on street corners, and there is no stopping them. I wouldn’t be surprised if the authorities know about it and are allowing the dealers to make this their stronghold. I myself have tried several times to control the situation but in vain. The police see it happening but do nothing.”

They are broken down like the place they come from. For these young people, this vicious cycle of depression, frustration, and angst only mirrors the lives led by their own families and communities. When will things change for them, no one knows.