Two nations and a black hole

For both Pakistan and India, Kulbhushan Jadhav has become a pawn in a high-stakes game.

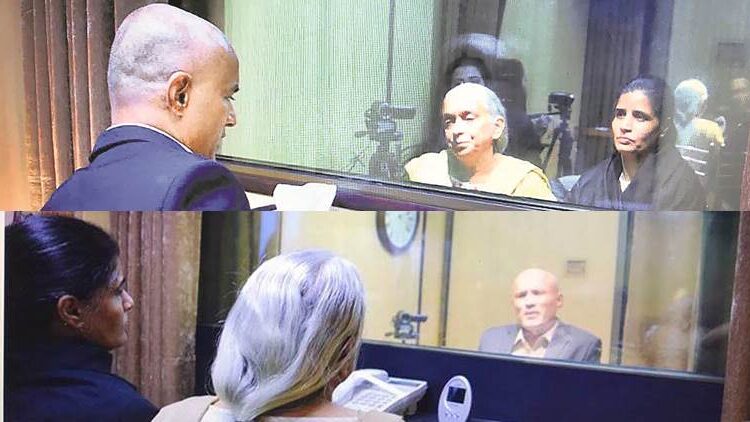

In my memory, the Pakistan Foreign Office in Islamabad has a bright foyer lit with a grand chandelier, and tea and biscuits were always laid out outside the weekly briefing room. There was the office of the minister upstairs, at that time Khurshid Kasuri, and a warren of other offices. As the first images of Kulbhushan Jadhav’s meeting with his mother Avanti and wife Chetankul came up on Twitter, it was hard to reconcile that memory with this bunker-type space with glass partition upon partition, where the conversation was conducted over intercom, and a clock ticked away ominously.

The theatre should not have come as a surprise. There is shock and outrage in India, and even some among well-meaning people in Pakistan, that the meeting took place under circumstances arranged to rob it of any meaning for the three main actors. But right from the time that Pakistan agreed to allow Jadhav to meet his wife, and then added on his mother, it should have been clear that this was going to be milked for what it was worth. Because this is the sad truth about India-Pakistan relations.

Individuals and their emotions do not count. They are mere pawns in the high-stakes game that both sides know how to play well. That is why they issue visas at will, and then, at will, stop issuing visas. This is why they arrest each other’s nationals and keep them in jails for years after they finish their sentences, releasing them only to make a political or diplomatic statement at a time of their choosing. This is why there can be cruelty to Sarbajit, and “humanitarianism” for Jadhav. This is why a mother and a wife became the latest pawns in this game on December 25.

A question is doing the rounds: Would India have behaved any differently had the boot been on the other foot? It is nice to think that it would have, but there is no guarantee, and those who know better about these things say the treatment might have been the same, perhaps minus the American-style partitions. As for Indian TV channels, it is not difficult to imagine them throwing the same questions. Come to think of it, in lending its voice to the outrage and accusing Pakistan of shortchanging the two women and subjecting them to harassment, New Delhi is also using them to further its agenda against Pakistan. Thus are constituencies of India-Pakistan created. That is the only thing for which people are required in this game — to keep the two locked in permanent hostility.

Jadhav’s day out with his family was Pakistan’s chance to offset the lack of credibility on his trial, which was held secretly in a military court — and it was always going to use it. According to a March 2017 report in Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper, since the courts came into existence in 2015, two months after the attack on the Army school in Peshawar, 274 people were convicted. Of these, 161 had been sentenced to death, 12 had been executed and 113 had been given life terms. These are not open trials, and there is no information on what specific charges are laid against a person until the case is decided and the person convicted. An article in the online news site, Diplomat, says 144 of the convicted had “confessed”, a high and improbable rate of confessions.

The choice of December 25, celebrated the world over as a day of peace and compassion, and in Pakistan also as the birth anniversary of founder Mohammed Ali Jinnah, was carefully chosen for the symbolism. But Pakistan’s insistence at every step that this was “a purely humanitarian” gesture begged the question if that was intended to convey a grand gesture or a narrow one. It was clearly both, aimed at two kinds of audiences — internationally, to signal that Pakistan had nothing to hide; and at home, to convey that this was no legal concession, but a gesture by a responsible state going out of its way to make a mother and son and wife happy, even if they were from the enemy country. And indeed, despite all its constraints, the meeting must have been important for the two Jadhav women; the alternative, to have never had that opportunity, is terrible to contemplate even after we know how the meeting went.

Pakistan’s decision to allow the meeting to take place gave the country a feel good moment about itself, to say, “Look, we are nice even to your spies”. For this is what Pakistanis, even those who value and stand up and speak for peace and friendship with India, believe — Jadhav was an Indian spy. And certainly, there are unexplained questions — about Jadhav’s second passport, the false name, the Muslim identity — which do not sit well with the Indian explanation that he was a trader in Iran.

In March 2016, when he was arrested and the military put out a confessional video, commentators in Pakistan, including anti-establishment voices, said Pakistan has laid its hands on “its own Ajmal Kasab”, with the crucial difference that Pakistan could shrug off the real Ajmal Kasab as a non-state actor, but Jadhav’s links with the Indian Navy made him a “state actor”.

All countries send out spies, and neither India nor Pakistan are wallflowers in this department. Undercover operatives are routinely arrested. Some are expendable or deniable and must fend for themselves if caught; for some, there have been secret talks between the intelligence agencies of the two countries and releases, perhaps even exchanges. And there are reports to suggest India has a Pakistani in its custody who could be exchanged for Jadhav in this way. But all that was ruled out the minute he became public goods, fought over by two hyper-national countries.

The case before the International Court of Justice may yet win consular access to Jadhav. But as the experience with Sarabjit showed, that may not help bring Jadhav back home. That only political goodwill can do. That would mean negotiations and a concerted effort at normalising relations. Both India and Pakistan have shown that they lack the will and the capacity for this. But let’s not forget too that states are but a reflection of the people who live in them. Fingers and toes crossed for Jadhav and his family and all others unlucky enough to get caught in the black hole called India-Pakistan relations.

Source: Indianexpress.com