Exclusion and ethnic strife: Story of Sri Lanka’s citizenship law

This story was first published in The Indian Express

Senior journalist and SAWM member Nirupama Subramanian writes about an important but not much discussed political issue – the Indian Origin Tamils. Even before independence the treatment of Indian Tamils used to cast shadow over India-Srilanka relation. Now when we are deep into Citizenship Law, it’s time we revisit this issue once again.

On December 18, a Home Ministry spokesperson seeking to address questions around the new citizenship law wrote on Twitter: “On different occasions special provisions have been made by Government in the past to accommodate the citizenship of foreigners who had to flee to India. E.g. 4.61 lakh Tamils of Indian origin were given Indian citizenship during 1964-2008.”

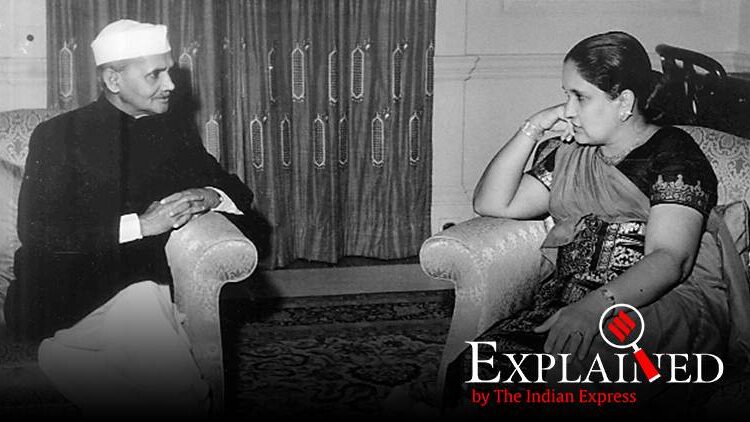

The reference was to the Indian Origin Tamils (IOTs) of Sri Lanka, and the Lal Bahadur Shastri-Sirimavo Bandaranaike Pact of 1964. The statement, though not accurate, highlighted unwittingly the disastrous consequences of exclusionary citizenship legislation enacted by Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) within months of gaining independence in February 1948.

Exclusion of the IOTs

Sri Lanka’s November 1948 Citizenship Act was the first in a series of divisive moves by the Sinhala ruling elites to consolidate their political base in the majority Sinhalese (Buddhist and Christian) community. It was aimed at excluding IOTs — then as now, the predominant workforce in the upcountry tea estates — whose numbers and growing association with leftist parties were proving to be politically inconvenient.

The IOTs that India accepted through the 1964 agreement were not “fleeing” Sri Lanka; most were, in fact, reluctant to leave the country in which they had lived for three generations or longer. Those that remained, were stateless in Sri Lanka for decades until their status as citizens was settled through amendments in Sri Lankan law in 1987, 1993, and 2003 — ironically because the ruling party now wanted their votes.

One of the immediate fallouts of the 1948 Act was the formation of SJV Chelvanayakam’s Federal Party (Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi). Its later avatar, Tamil United Liberation Front, demanded a separate Eelam in 1976 in its famous Vadukoddai Resolution. The rest, as they say, is history.

Political scientist Amita Shastri noted that the Citizenship Act sharply delineated ethnic differences, and distorted the political system to weight it in favour the Sinhalese majority. “This created an intractable dynamic of ethnic outbidding between the two major Sinhalese-dominated parties [the United National Party and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party] to attract Sinhalese [voters] at the expense of the Sri Lankan Tamil minority. This directly contributed to the latter’s alienation, support for secessionism, and the outbreak of ethnic violence and civil war in the 1970s and 1980s.” ( ‘Estate Tamils, the Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948 and Sri Lankan Politics’ (1999) Contemporary South Asia, 8:1, 65-86)

The Indian Origin Tamils

Different from Sri Lankan Tamils who live predominantly in the North and East, the IoTs are descendants of indentured Tamil workers whom the British shipped to the island in the mid 19th century to work on tea estates in the five hill districts of the Central and Uva provinces. These people now call themselves Malayaha (hill country) Tamils — because of the historical stigma attached to being “Indian” Tamils.

At the time of Sri Lanka’s independence, the IOTs numbered around 800,000. They were the backbone of the tea industry, politically active, and keen to ensure their rights in independent Sri Lanka through strategic alliances with unions and left parties.

Ahead of independence, Sri Lanka’s ruling classes had held fraught discussions with the British on questions of citizenship, franchise, and the rights of minorities. In the 1947 elections to the Ceylon legislature, the IOTs represented by the Ceylon Indian Congress allied with the All Ceylon Tamil Congress (representing the Sri Lankan Tamils) and the left parties. The CIC won 7 seats, helped the left parties win 14, and influenced results in 5 or 6 other seats. The Sinhalese elite-dominated United National Party won 42 out of the 95 seats.

Determined to blunt their political clout, the UNP described IOTs as “birds of passage” with no loyalty to the country, as India’s fifth column in Sri Lanka, and as people who stole the locals’ jobs. Sri Lanka’s first Prime Minister D S Senanayake rushed the Citizenship Act through the legislature just seven months after independence.

The Citizenship Act

Under the Act, citizenship could be only by patrilineal descent or registration. For citizenship by registration, umarried persons had to show 10 years of uninterrupted stay in Sri Lanka from the date of application; married persons had to show 7 years. Most IOTs were unlettered and poor, with no documents. Effectively an entire community was rendered stateless.

Soon afterward came the Indian & Pakistani Residents’ Act of 1949, which opened a window for those above a certain income level.

Finally, the 1949 Ceylon (Parliamentary Elections) Amendment was passed, under which only citizens could vote. The IOTs were stripped of voting rights, and the fallout was immediate: in 1947, there were 7 Indian Tamils in the legislature; in 1952, there were none.

The Citizenship Act triggered panic similar to that seen in Assam during the National Register of Citizens (NRC) process. By August 5, 1951, when the two-year deadline for applications for citizenship ended, 2,37,000 applications had been filed, covering most of the 8,24,430 Indian Tamils. By 1964, with the natural increase in population, the number of stateless IOTs reached nearly 10 lakh. Only 1,40,000 had been granted citizenship under the Indian & Pakistani Residents’ Act, and 2,50,000 were accepted by India as its citizens.

India-Sri Lanka relations

The treatment of Indian Tamils had cast a shadow on India-Sri Lanka relations even before independence; post-independence, the citizenship laws became a major irritant. They were denounced in India, and the Madras legislature passed a resolution against them. In 1947, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had tried unsuccessfully to persuade Senanayake to give citizenship to all Indian Tamils who had lived in the country for 7 years prior to January 1, 1948. The two countries corresponded on this issue until Nehru’s death in 1964. Nehru rejected the Sri Lankan position that the “stateless” IOTs were automatically Indian citizens, and would have to be shipped to India.

After the 1962 war with China, Prime Minister Shastri was eager to mend fences with Sri Lanka. He gave in to Bandaranaike’s demands, and it was agreed that Sri Lanka would accept 3,00,000 IOTs and their natural increase, while India would accept 5,25,000 IOTs and their natural increase. The status of the balance 1,50,000 IOTs was to be decided later.

Some 4,00,000 reluctantly applied for citizenship of India; 6,30,000 applied for Sri Lanka’s. By the time the window agreed upon in 1964 closed, only 1,62,000 IOTs had been given Sri Lankan citizenship. In the same period, India gave citizenship to over 3,50,000.

Sinhala-Tamil tensions

Majoritarianism had by then taken firm root in Sri Lanka’s politics. In 1956, SWRD Bandaranaike, who had broken from the UNP to form the Sri Lanka Freedom Party in 1951, became Prime Minister on the Sinhala Only plank, which then became the Official Language Act. There were protests by Tamils, and Chelvanayakam’s Federal Party demanded a new federal constitution with autonomy for the Tamil dominated north and east, and the scrapping of the Citizenship Act. The 1957 “Banda-Chelva agreement” followed, which the UNP opposed strongly. Ethnic riots broke out, and SWRD tore up the agreement.

But the ethnic crisis was now out of control. In the coming decades it would morph into the LTTE’s bloody war for independence. By the time the war came to its terrible end in 2009, tens of thousands of Tamil civilians had been killed, and both Tamils and Sinhalas had suffered irreparably.

As for the IOTs, as the two major Sinhala parties came to realise the value of the chunk of their votes, substantive changes were made to the law in 1993 and 2003 to absorb them as citizens of the country.

The decades-long absence of political representation, however, led to the complete exclusion of Indian Tamils from the Sri Lankan national imagination. The community became poorer, lacking access to education, better living and work conditions. Until almost the end of the 20th century, they had the worst human development indices of any ethnic community in Sri Lanka. Small improvements have been registered since.