Myanmar in the balance: West must beware sledgehammer sanctions, which will snuff out the democratic spirits

This story first appeared in Times of India Blog

The world – certainly India – has deep stakes in Myanmar. Let’s acknowledge this reality before rushing to consign our next door neighbour to perdition after last week’s coup.

Yes, the generals are back in Naypyidaw. They had never really left, they had merely made space for a civilian whose popularity and trajectory unsettled them. The guns won, on a day when parliament was to open with an overwhelming victory by Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD party. The reasons for the coup range from the junta alleging electoral fraud to their fear that Suu Kyi would undermine the constitution and their predominant role in the country. One or all of these may be correct.

Asean, itself replete with authoritarian regimes, issued a muted chair statement. India, being the only large democracy next to Myanmar, has urged a return to the democratic process and rule of law. So has Japan. The Japanese state defence minister Yasuhide Nakayama gave voice to caution: “If we stop, the Myanmar military’s relationship with China’s army will get stronger, and they will further grow distant from free nations … I think that would pose a risk to the security of the region.”

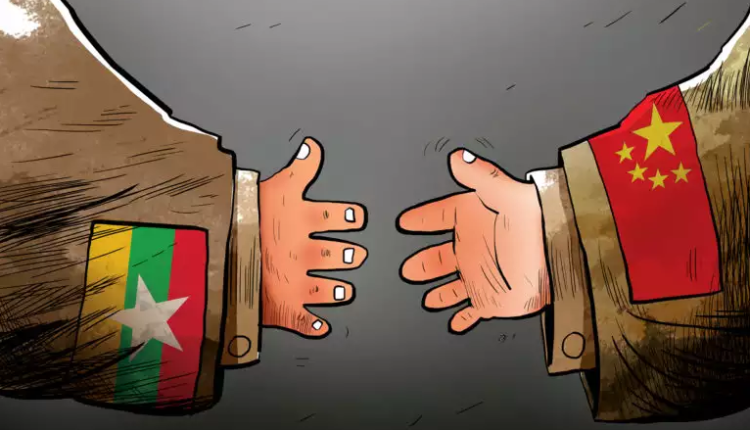

The thing is, Myanmar doesn’t react well to international pressure. If Myanmar is not allowed to diversify its engagement, it will end up once again in a toxic relationship with China, to the detriment of everyone else in the region. It needs reminding that in 2010, it was the Myanmar junta’s decision to reduce their dependence on China that led to the opening up of the country. The world only woke up when the junta cancelled the Myitsone dam project by China.

In the past five years China has made nice with Suu Kyi, being the first to accord her head of state status. China has relentlessly pushed both its mercantilist agenda and its Belt & Road Initiative. Ethnic groups have accused Suu Kyi and the NLD of doling out controversial deals to the Chinese in a manner not dissimilar to the way the military rulers handled things.

On the other hand China is building a border fence in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in the Shan state, which Myanmar says violates the 1961 border protocol. Separately, China funds and arms ethnic armies in Myanmar, even as they offer to help in peace negotiations. The Arakan Army is one, but their biggest proxies are the United Wa State Army. In recent months the Arakan Army have attacked Indian workers in the Kaladan multi-modal project, several have had to be rescued from AA kidnappers.

Senior general Min Aung Hlaing, the man currently in charge of Myanmar, appealed for help in an interview in Moscow in June, 2020. Referring to these ethnic armies, he said, “If we can cut them off their support, they will be weakened. This cannot be done by a respective individual country alone. It is necessary for other countries to help that country. Terrorist acts cannot be committed by an organisation with only one stance. There is support behind them financially. They have providers of weapons, ammunition, rations, cash and recruits.”

India learnt its lesson in the 1990s with regard to Myanmar. Then too, PM Narasimha Rao took a more realistic approach, even staying away from a Suu Kyi award ceremony (as recounted by G Parthasarathy). Over the years India has developed a unique two-track engagement with that country. In 2009-10, India worked hard with the US – former diplomat Gautam Bambawale and Kurt Campbell (currently Biden’s Indo-Pacific czar) – to impress a different approach to Myanmar.

In 2020, foreign secretary Harsh Shringla travelled together with army chief MM Naravane to Myanmar to show New Delhi treats both arms of the government there equally. Myanmar featured prominently in Monday’s Modi-Biden conversation as the Indian PM sought to caution Washington on sanctions.

Interestingly, Myanmar opted for an Indian submarine and Indian vaccines. As China has pushed its weapons, Myanmar has gone to Russia for choice. Myanmar has continued to play all sides – in the past decade Japan, India, Russia, Indonesia and Singapore have deepened their engagement in Myanmar recognising its geo-strategic importance. The West dealt themselves out of Myanmar after the 2017 Rohingya crisis. China inserted itself early as a mediator between Myanmar and Bangladesh, but achieved little. India took a more humanitarian approach, by providing relief to the Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar as well as building homes in Rakhine province.

In fact, instead of hyperventilating about the military takeover, we should all put heads together to find an equitable solution to this ticking time bomb. Bangladesh is straining at the seams, and security reports say these camps could be spewing out radicalised young men and women – if they make their way to Pakistan we know the outcome; if they end up in Southeast Asian countries, there’s another crisis, not to speak of what will go through Bangladesh and India.

The Biden administration could, even for domestic politics, throw sanctions at the military. That would be short-sighted. First, no ruling authority has suffered under sanctions, it has always been the average citizen. Second, Myanmar has attracted investments and Asian companies in the past decade. Sanctions will drive them away, it cannot be anyone’s case that Myanmar has to return to isolation. Third, Asia will continue to engage Myanmar. The West will be out of a key part of the Indo-Pacific. Protests have broken out across Myanmar, which shows democratic spirit has certainly taken root. It would be a shame to snuff this out with sledgehammer sanctions.