600 Indian fishermen will find their way back home this month

This story first appeared in Voicepk.net

“While both India and Pakistan periodically release large numbers of prisoners as gestures of goodwill there appears to be no streamlined process that ensures the rights of foreign prisoners are systematically upheld rather than on an ad hoc basis,” says Haya Zahid.

Prompted by its Foreign Minister’s presence in Goa for the Shanghai Corporation Organization (SCO) as well as a campaign launched by the National Commission of Human Righs (NCHR), Pakistan has instantly signed the release of 200 Indian fishermen from its prisons on Thursday, May 4 as a ‘goodwill gesture’. To follow, the remaining 400 will be released by May 14.

According to reports, there continue to be 705 Indian prisoners who are detained in Pakistan, out of which 654 are from the fisher folk community – the poorest of the poor among the countries’ socioeconomic classes.

The repatriation campaign was launched on May 1, by Rabiya Javeri Agha, the chairperson of the National Commission for Human Rights (NCHR), under which their ordeal was highlighted. Fisherfolk in general are imprisoned by authorities on either side for accidentally crossing – often due to sea storms and invisible maritime borders. NCHR also reiterated in its campaign national and international agreements that applied to such prisoners and urged the governments of Pakistan and India to schedule talks to ensure the return of the detained fishermen.

Then on Thursday, May 3, in a joint statement released in New Delhi, the National Fishworkers Forum (NFF) and the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace & Democracy (PIPFPD) jointly requested the Foreign Minister of Pakistan, Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari and the External Affairs Minister, India, Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar to take action on the release of the arrested fishermen.

Rights organizations on both sides say that today’s move by Pakistan is a positive development ahead of the SCO. Human rights groups on both sides have often urged the governments for a ‘no-arrest’ policy for fishermen.

‘No one crosses by choice’

In Pakistani waters, foreign fishermen are intercepted by the Maritime Security Agency before being criminally charged and confined in prison pending the conclusion of their cases.

Meanwhile, India has 434 Pakistani prisoners in custody, including 95 fishermen.

Ramkrishna Tandel, a member of India’s fisherfolk forum said that no fishermen crosses international maritime borders by choice.

“Many fishermen cross the borders inadvertently due to storms, high-tide, low-tide or unseen maritime borders,” he said. “They should not be arrested but rather pushed back into the waters of their home countries. And they should certainly not be fired at.”

Prominent Indian activist for the rights of the fisherfolk, Jatin Desai has welcomed the release of the Indian fishermen by Pakistan. He says that this kind of action can and will help ease tensions between the countries.

Hundreds imprisoned on both sides

In their joint letter to the foreign ministers on both sides, the NFF and the PFF highlighted on May 3 (before the release of the 200 inmates) that 654 Indian fishworkers were in Karachi’s Malir Jail, 631 arrested fish workers had already completed their sentence and their nationality was also verified, 83 Pakistani fishworkers were in Indian jails, and many of them had completed their sentences with their nationality verified.

Not releasing them after they have completed their sentenced term and spent many years post-completion violates the Agreement on Consular Access of 2008. As agreed by both countries in 2008, the Agreement on Consular Access, Section 5 of the Agreement says, ‘Both Governments agree to release and repatriate persons within one month of confirmation of their national status and completion of sentences.’

“Today is a wonderful day because we look forward to the return of the Indian fishermen to their homes and we look forward to our fishermen back to their families,” said Rabiya Javeri Agha, in an exclusive interview with Voicepk.net. “They went out to earn a livelihood and suddenly ended up incarcerated without daily contact with their families. We need to look at a proper way forward and activate a council of policies so that the poor and the vulnerable do not have to face the hardships that they do.”

‘The issues remain the same.’

Barrister Haya Emaan Zahid, Secretary of the Sindh Government’s Committee for the Welfare of Prisoners, has been providing legal aid for the past 20 years to vulnerable prisoners. She is also working on locating the families of the arrested Pakistani fishermen.

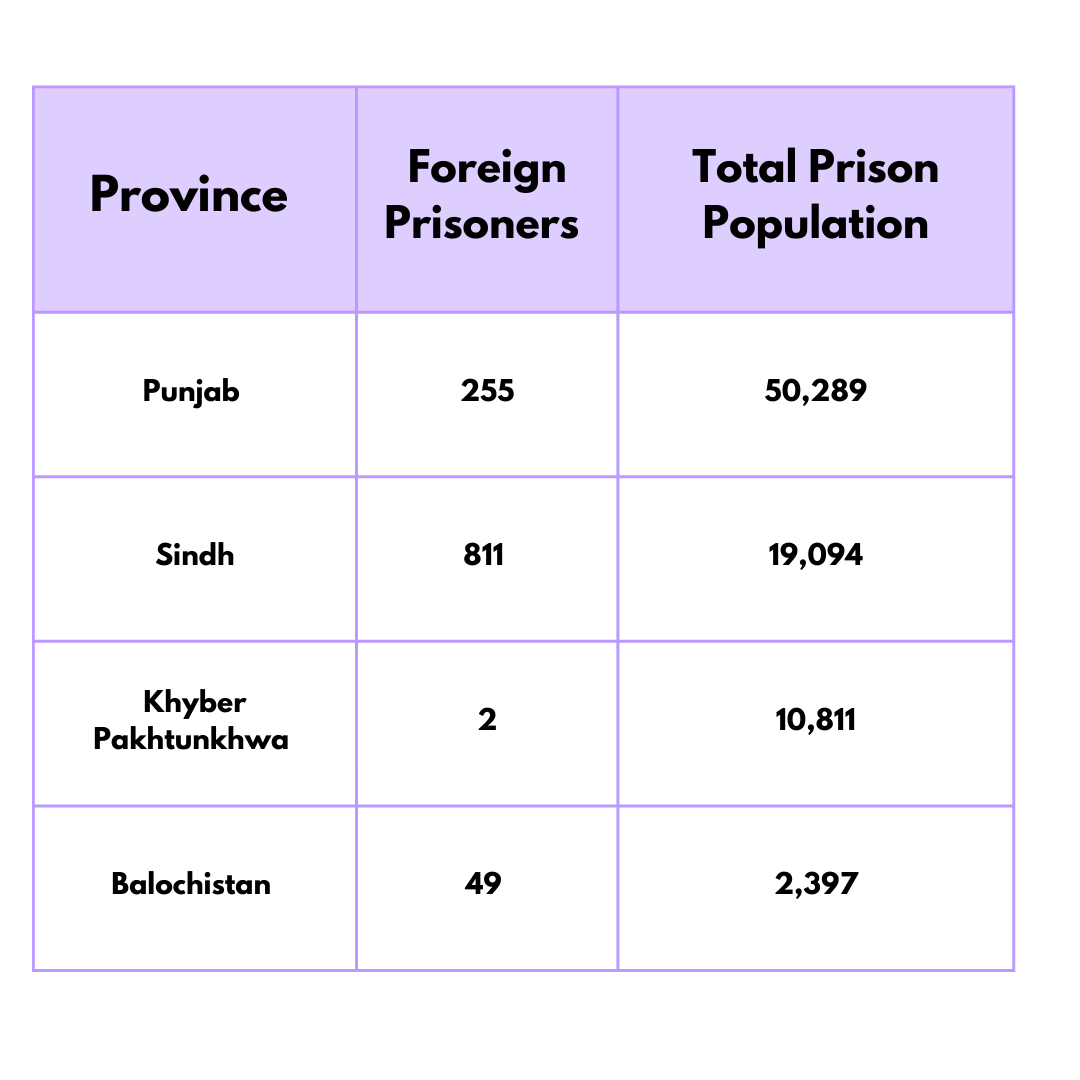

“In 2020 we mapped out the number of foreign prisoners who were in Pakistani jails and we discovered the majority of them were Indian fishermen,” she said. “Though the numbers have changed now, it remains relevant because the issues remain the same.”

To address the persistent problem of Indians and Pakistani fishermen getting arrested in foreign waters, the two countries signed an Agreement on Consular Access in 2008 which mandates that each country will provide the other’s nationals with consular access within three months of arrest and detention, a step necessary to begin the process of verifying nationality without which repatriation is impossible.

The three-month time range applies to Indian fishermen as a result of the Consular Agreement between India and Pakistan, but prisoners from all foreign countries are guaranteed the right to consular visits pursuant to the Vienna Convention to which Pakistan is party.

Repatriation

The process of repatriation after the completion of sentences points to other issues. In practice, timely repatriation is an extremely complex process that requires coordinated efforts by the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the various agencies and ministries of the foreign countries in question.

On the Pakistani side, the Federal Review Board, which consists of a panel of Supreme Court justices, convenes meetings every few months to obtain an update from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior about the status of foreign prisoners’ repatriation. The Joint Judicial Committee which had been formed in 2008 consisted of retired judges from both countries whose mandate was to meet every six months, seek early repatriation of prisoners whose sentences were complete, and ensure that the basic human rights of all such prisoners were upheld by both countries.

But the committee’s inactivity since 2016 due to government delays has affected the issue. While India’s Ministry of External Affairs has nominated judges, and while Pakistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has greenlighted the Committee’s reconstitution, Pakistan has yet to nominate judges.

“While both India and Pakistan periodically release large numbers of prisoners as gestures of goodwill there appears to be no streamlined process that ensures the rights of foreign prisoners are systematically upheld rather than on an ad hoc basis,” said Haya Zahid.