Adani’s global footprint and India’s infrastructure diplomacy

This story first appeared in The Indian Express

From mines to ports and logistics, the Adani conglomerate has been expanding across sectors, regions. This has gone hand in hand with India’s diplomatic and strategic outreach

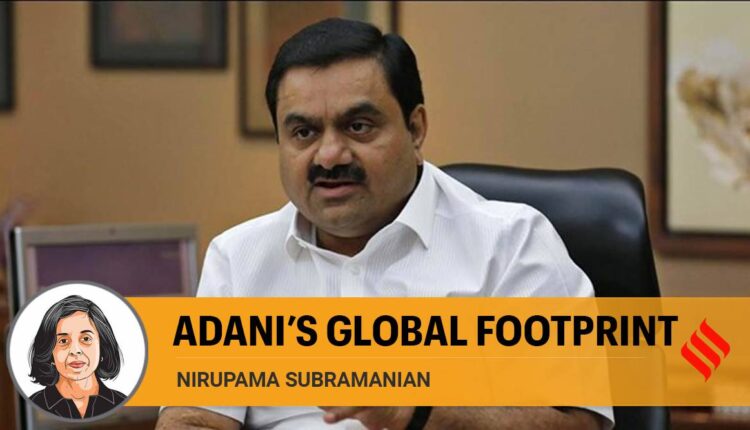

“Several foreign governments are now approaching us to work in their geographies and help build their infrastructure. Therefore, in 2022, we also laid the foundation to seek a broader expansion beyond India’s boundaries,” chairman and founder of the Adani group Gautam Adani, now the world’s third-richest person, said in a virtual address to shareholders at the annual general meeting of Adani Enterprises Ltd in July this year.

In fact, the Adani group had been scouting abroad much earlier. Since 2010, the Adani group has been in Australia, developing the Carmichael coal mine in Queensland despite massive country-wide protests over environmental and other concerns. The mine is now operational, albeit not as big as planned and, it has begun exporting.

In 2017, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zones (Ltd) signed an MoU for a greenfield multi-purpose port for handling containers at Carey Island in Selangor state, about 50 km southwest of Kuala Lumpur. With Malaysia a crucial link in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, the Adani interest was contrary to the expectation that a Chinese investor would be roped in for a mega port-cum-maritime city project on Carey Island. Like Carmichael, however, the port project ran into local opposition. A feasibility study is still ongoing.

The last two years, however, have seen the company pursue international infrastructure projects aggressively. In May 2022, APSEZ made a winning bid of $1.18 billion for Israeli state-owned Haifa Port, jointly with Israeli chemicals and logistics firm Gadot. The Adani company will own 70 per cent of the stake in the port. Down the road from Haifa is another port operated by the Chinese state-owned Shanghai International Port Group, and the two are expected to compete for business.

In August this year, APSEZ and Abu Dhabi’s AD Ports Group signed an MoU for “strategic joint investments” in Tanzania. In their sights is Bagamoyo Port, earlier being jointly developed by China Merchants Holdings International and Oman’s State Government Reserve Fund (SGRF) under a 2013 agreement with the Tanzanian government. The port was supposed to be a premium BRI project. But it struggled to get off the ground. Two years ago, the contract was cancelled after then President John Magufuli called the terms “exploitative and awkward”. The new ASEZ-AD MoU will look at a bouquet of infrastructure projects besides Bagamoyo in the East African Indian Ocean nation — rail, maritime services, digital services and industrial zones.

Is it just a coincidence that Adani’s global expansion closely shadows the Chinese footprint along its Belt and Road Initiative? Or is it that as Delhi competes with China for influence in the neighbourhood and beyond, the Adani group’s size, resources and capacity are seen as a key element in achieving India’s strategic objectives than has been possible so far. Irrespective, India’s infrastructure diplomacy is now becoming identified the world over with one company.

For the Adani group, described as India’s biggest ports and logistics company, there couldn’t be a better time. As the Quad grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the US, competes with China in the Indo-Pacific, it has committed “to catalyse infrastructure delivery” by putting more than $50 billion on the table for “assistance and investment” in the Indo-Pacific over the next five years and “drive public and private investment to bridge gaps”. The Australia-India free trade agreement signed earlier this year, which gives coal imported from Australia zero duty access to India, is no small detail for Adani.

The joint Adani-AD Ports interest in Tanzania has come at a time when India-Israel-UAE-US have come together as the “Quad of the middle east” to address the China challenge outside the Indo-Pacific.

In Sri Lanka, a controversy erupted over last year’s award of two wind energy projects to Adani Green Energy Ltd, after an official declared he had been asked to greenlight the project by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa under pressure from the Indian Prime Minister.

It was not the first time though that Adani appeared as the go-to company for Indian projects in Sri Lanka.

Under a Sri Lanka-Japan-India agreement, APSEZ was to develop and operate the East Container Terminal at Colombo Port. The Rajapaksa government abruptly cancelled this agreement in January 2021, and later offered the West Container Terminal as consolation. Adani is developing it jointly with a Sri Lankan partner. In both cases, it is not known why or through what process Adani was the chosen Indian developer.

Even as many in Sri Lanka fret about these “secret agreements”, Sri Lankan officials seem to have made pragmatic peace with the choice. “80 per cent of the business at Colombo Port is transhipment. Of this, 70 per cent is to India. And of that 70 per cent, 35 per cent goes to Adani held ports. With Adani coming in with 3 million TEUs (20-foot equivalent unit) in the West Container Terminal — our capacity of 7.5 million TEUs increases significantly,” Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner to India Milinda Moragoda said in an interview to The Indian Express in January.

Adani’s new “no-hands” model of doing business with neighbours — a power plant in Jharkhand, exporting all its output to Bangladesh — has been seen as a “win-win” deal. An official compared the “success” of this model with Nepal, where Indian projects have been held up for decades due to local politics and other hurdles. Jharkhand was not problem free, but as Adani tweeted after his meeting with Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in Delhi earlier this month, the project is all set to send 1500 MW to Bangladesh by Bijoy Dibosh in December 2022, six years after an MoU for this was signed.

The link between diplomacy and commercial interests has generated its share of debate, especially in the US, where its diplomats, intelligence agencies and military interventions abroad have actively pushed the interests of big business — first the hunt for cheaper raw materials, then for markets abroad, then to shift industry where manpower was cheaper. As seen in the new age trading blocs — the US-led IPEF, and the Chinese dominated RCEP — economic interests lie at the heart of geopolitics.

At a time when global rivalries are growing sharper in the shadow of the war in Europe, and as India looks out for its own interests, pushing powerful corporates to the centre-stage of its diplomacy, whether it is to build ports, buy or sell weapons or make chips, is inevitable. Which companies are deployed, how and why will be watched and discussed. Just as Delhi has fashioned non-alignment 2.0 in its global relations, its diplomacy has to avoid tying itself, and by extension the national interest, in less than opaque ways to the fortunes of a single private entity. Given the concentration of capital in India Inc and the economic headwinds ahead, that will be a challenge.