Benodebehari Mukherjee: Blind Indian painter’s forgotten scroll found after 100 years

This story first appeared in BBC News

A 44 foot-long Japanese style handscroll painted by a famous Indian blind artist nearly 100 years ago has resurfaced and gone on public display for the first time in the city of his birth, Kolkata.

Benodebehari Mukherjee, born in 1904, was blind in one eye and severely myopic in the other. He lost his vision entirely at 53. Mukherjee, who died in 1980, created trailblazing works as a painter of landscapes and frescos. He was also a sculptor and muralist and came to define modern art in 20th Century India.

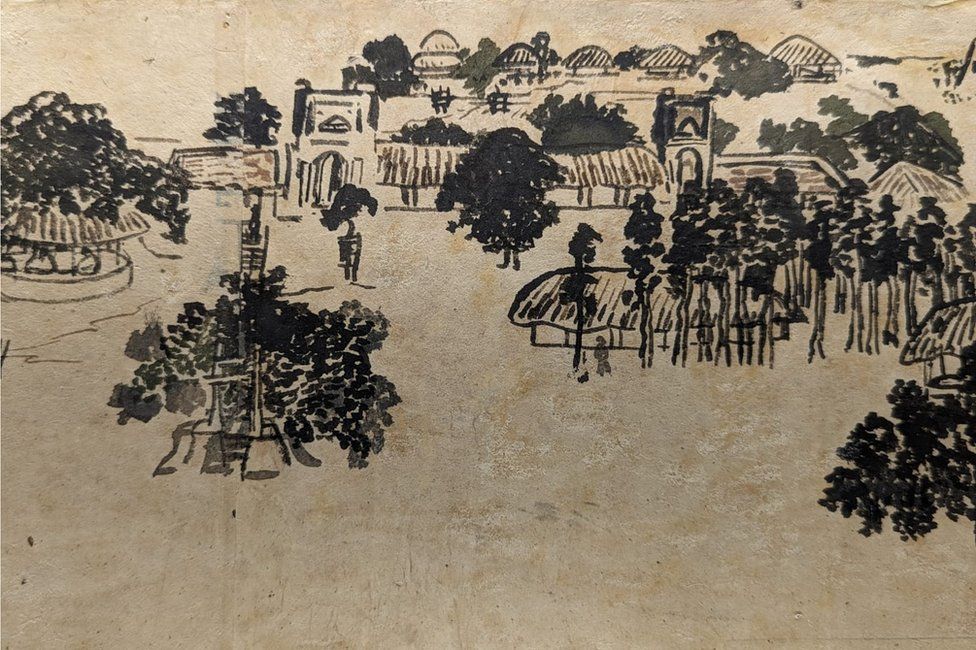

In July, the scroll – which is just six inches wide – will travel to Santiniketan, the university town founded in West Bengal a century ago by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, where Mukherjee was a student and later a teacher. The scroll, the longest that the artist created, is titled Scenes from Santiniketan.

The scroll changed hands twice before reaching its final destination in Kolkata where it’s currently at display.

Mukherjee, it seems, either gifted or sold the scroll to Sudhir Khastagir, an art school graduate in Santiniketan as early as 1929. Khastagir later moved to Dehra Dun to join a leading school as an art teacher. He gifted the scroll to another artist, who eventually sold it to Rakesh Saini – an archivist and owner of an art gallery in Kolkata – six years ago for an undisclosed amount.

At the age of 20, Mukherjee had crafted this captivating scroll using ink and watercolours on meticulously layered sheets of paper. The first frame has a figure sitting under a tree which could be the artist himself who takes the viewer on a journey through Santiniketan. This is a frequent motif in Japanese and Chinese scrolls where strategically placed figures guide our viewing.

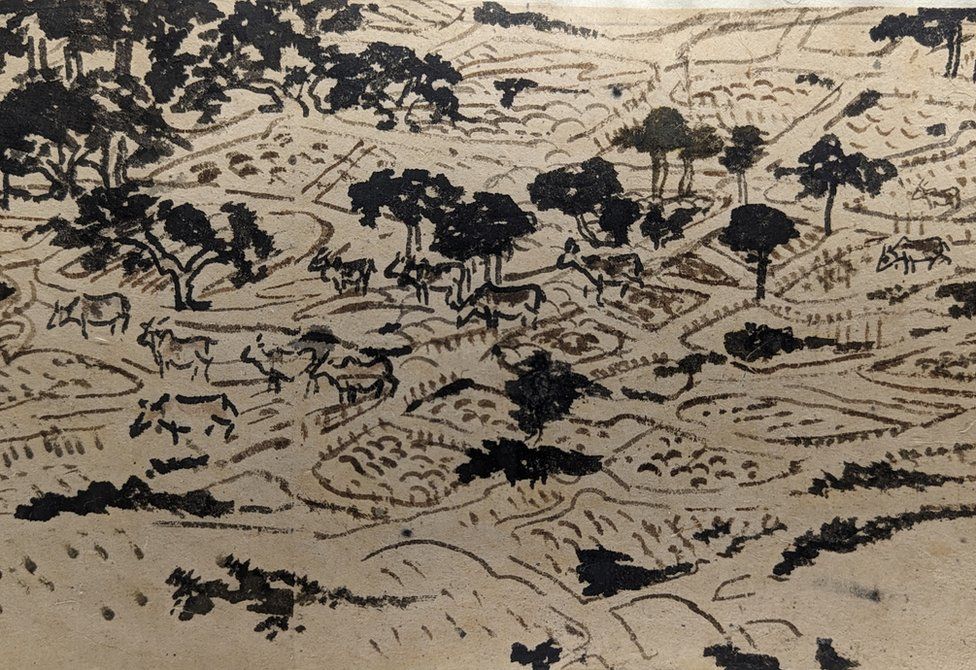

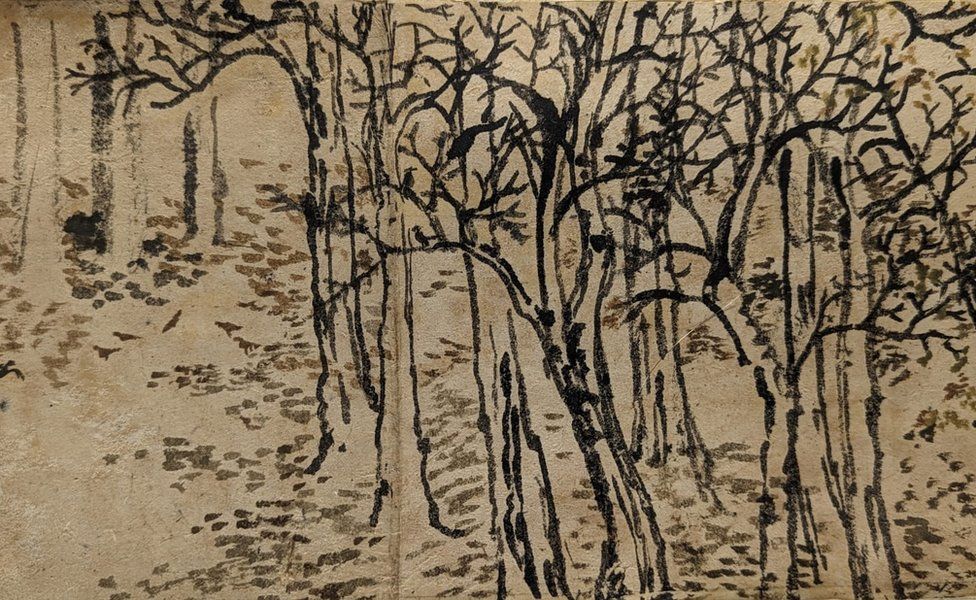

As the viewer moves from right to left, a journey unfolds through time and space, guiding her into a forest of sal trees depicted in black ink, gradually transitioning to touches of green that mirror the changing seasons.

A man on a bullock cart trundles by. The viewer stops at a village where they are boiling the sap of date palms to make toddy, a local brew. The ripening paddy turns the rice fields into light light green hues, while the once-lush tree leaves transition into an autumnal brown. Winter arrives, bringing a kind of desolation that is captured in the last frame depicting the khoai, a canyon-like terrain of laterite soil near Santiniketan

The scroll has 22 human figures, 22 cattle, three chicken, one dog and one bird. There are stretches of emptiness that Mukherjee uses to depict land and sky.

Pervasive in the scroll is the artist’s “solitude, a sense of isolation subtly expressed and presented…as a state of his life, without self-pity or bitterness,” notes Siva Kumar, a leading art historian. The scroll, he says, “bears all signs of the artist’s genius that flowered in the coming years”.

Till it surfaced, Mukherjee’s longest work was a depiction of the khoai, which was painted in the mid-1930s and is just over 10-feet long.

Mukherjee’s teacher at Santiniketan was one of India’s greatest artists, Nandalal Bose, who headed Kala Bhavan, the art school. Bose had expressed concern to Tagore about a visually impaired art student, says Siva Kumar. Tagore replied, “Is he sincere? Is he interested? Then let him be.”

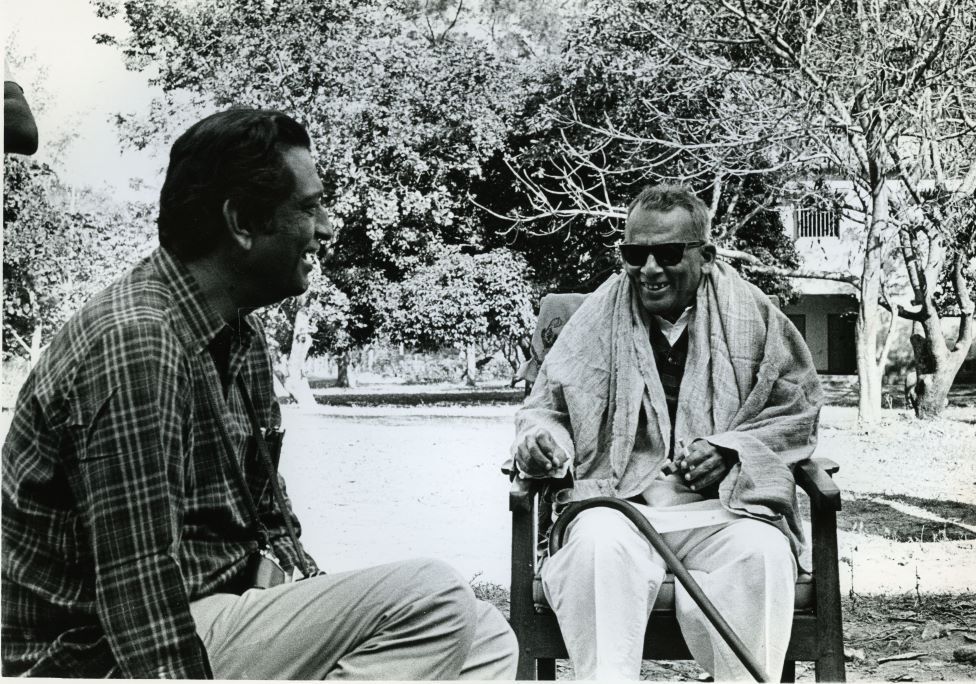

Almost as famous as his mentors were Mukherjee’s students at Kala Bhavan. Among them were artists such as KG Subramanyan and Somnath Hore and Oscar-winning filmmaker Satyajit Ray. In 1972, Ray made a documentary on Mukherjee called The Inner Eye. The moving tribute pitchforked the reclusive artist and his works onto the global stage.

Mukherjee was possibly inspired by prints of handscrolls that Tagore and Bose had brought back from their visit to Japan. “Mukherjee was specifically interested in the format of the scroll, an art form that has certain possibilities which other forms don’t have like [showing] the passage of time,” says Siva Kumar.

“You can recreate the experience of walking through a landscape rather than just standing somewhere and looking at it. In normal landscapes, you fragment nature. But in a handscroll you can show continuity and transformation.”

So where did the Scenes disappear for nearly a century?

Rakesh Sahni, owner of Gallery Rasa in Kolkata, acquired the scroll from from a collector in 2017. “I could have exhibited it earlier,” says Mr Sahni, “but I lost three years to the pandemic.”

At the Kolkata show, also on display are reproductions of Mukherjee’s other scrolls, including The Khoai, Village Scenes, and Scenes in Jungle. The last is painted on the semi-circular pith of a banana tree and is owned by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

Mukherjee’s other famous works are at Santiniketan: frescos on walls and ceilings of buildings in and around Kala Bhavan. Perhaps the most famous, the Lives of Medieval Saints on the walls of Cheena Bhavan – a Sino-Indian cultural studies centre – is almost eight feet tall and sprawled across a magnificent 80 feet. The frescos and scrolls were done well before the artist lost his vision.

After surgery destroyed his functional myopic eye, Mukherjee continued till the end to churn out murals, collages and sculpture with the same artistry as works he had created when he could still see with that one eye.

Ray’s documentary quotes a rare comment by Mukherjee on his impaired vision.

“Blindness is a new feeling, a new experience, a new state of being.”

That, perhaps, is Mukherjee’s best epitaph.