Delhi takes control of India-Pakistan narrative

This story first appeared in The Times of India

There appears to be a growing realisation among the upper echelons of Pakistani decision-making apparatus that the country’s strategic trajectory is unsustainable

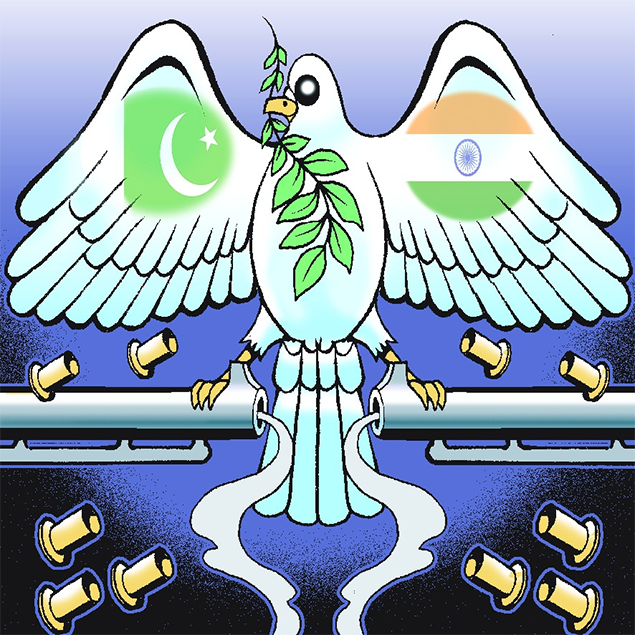

India-Pakistan watchers have had it easy for some time. The grim official silence between the two warring neighbours — stretching from the Pathankot airbase terror attack (January 2016) to the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu & Kashmir — meant that the hardline view was the accepted line on both sides of the border.

But 2021 has brought a different flavour in the breeze blowing through the borders. On February 25, the two sides reaffirmed a 2003 ceasefire. The past couple of years of ceaseless firing across the Line of Control (LoC) has been a drain on both sides. 2020 saw 5,133 instances of ceasefire violations, resulting in loss of lives of military personnel and civilians. The new ceasefire is therefore a welcome development regardless of how long it lasts. According to reports and anonymous sources, talks between National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval and Pakistan Army Chief General Qamar Bajwa were on quietly for some time and have now culminated in the ceasefire.

The ceasefire will be watched carefully until at least July/August, since these are typically peak infiltration months when Pakistan uses cover fire to push in terrorists into Kashmir. So far, this year, the numbers are reassuringly low. But snows are just melting and no one knows what the summer may bring.

All through March, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Pakistani counter-part Imran Khan have exchanged positive vibes — Modi sent a “happy Pakistan day” letter, Imran responded. Modi had kind words for the Pakistani delegates at a SAARC health meeting, and the he sent ‘get well soon’ wishes when Imran tested positive for Covid-19. Also, the Indus Water Commission met after a long time.

Finally, the actual ruler of Pakistan, Army Chief General Qamar Bajwa, said on March 18 that Pakistan wanted peace with India. Keeping J&K securely at “the head” of the problems between the two countries, he inserted a new term in the bilateral discourse, geo-economics. He prefaced a regional economic and connectivity vision with a resolution on Kashmir, but the general tone was a recognition of new realities that Pakistan must reconcile with. Almost on cue, last week, Pakistan’s Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) approved a proposal for Pakistan to import cotton and sugar from India, a big step. But Imran the commerce minister took the proposal to the cabinet where it was vetoed by Imran the prime minister. Round One went to the status-quoists.

Traditionally, the military-intelligence establishment has stepped in when politicians have reached out to India. This time, it seems, it’s the other way round. This is why the cabinet’s “opposition” may not stand scrutiny. None of the ministers, who opposed the opening of imports, has a political future without the army’s blessing, and that includes Imran. The move and the counter-move could be an attempt by the Imran government to insulate itself from political criticism, particularly from the opposition Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz Sharif and the Pakistan People’s Party. The u-turn could also mean that some powerful elements within the military-jihadi establishment still need to be brought around. Or, may be, Pakistan is still looking for a face-saver on Kashmir.

Nevertheless, there appears to be a growing realisation among the upper echelons of Pakistani decision-making apparatus that the country’s strategic trajectory is unsustainable. Afghanistan could soon revert to some kind of civil war between the Taliban and the Afghan government when the US forces leave. That will have a huge spillover effect on Pakistan’s own security — in recent months the Pakistan Taliban (TTP) has ramped up its activities. In addition, Pakistan, which sought to be a geo-political “bridge”, dreaming of leveraging its geographical position for geopolitical advantage against India, has found the going almost impossible in recent years. Pakistan’s use of terrorism as a state strategy has rebounded in ways those in charge had not bargained for. Pakistan has now been on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey list for the past couple of years, always teetering on the edge of the blacklist. June will see yet another review. Pakistan is too important to be pushed into the blacklist, but it’s hard to see how it can get off the grey list.

Pakistan had turned to China, almost becoming a protectorate of the Middle Kingdom, particularly through the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). But Pakistan mourns the loss of being the US’ strategic ally. Now Pakistan finds itself caught in the pincer of a new US-China Cold War. It has lost the primacy it enjoyed with Saudi Arabia and UAE. Turkey, Pakistan’s premier Islamic ally at the moment, is a bad word now, not only in parts of the Arab world but also in the US.

Repairing relations with India is a bitter pill, but one that may become inevitable for Pakistan. This week, Pak commentators felt slighted they were left out of Joe Biden’s climate summit; that Pakistan was included in a ‘red-list’ of countries along with Bangladesh and Philippines, barred from travelling to the UK; worse, that Pakistan’s U-turn on imports did not merit a comment from New Delhi.

Pakistan’s economy, despite Imran Khan’s protestations to the contrary, is in a perilous condition. A searing critique made it clear why geo-economic dreams for Pakistan is a bridge too far without deep structural reforms, some of which involve a more normalised economic relationship with India. India, naturally, is not overly concerned over Pakistan’s U-turn, which is why there was no official reaction.

The ceasefire agreement of February 25 is seen as a positive outcome for both sides, certainly from the Indian perspective. After a year of staring down both Chinese and Pakistani armies, India was a bit stretched. India also wanted to ring-fence its relations with Pakistan, by keeping the controls at the bilateral level. With Joe Biden at the helm in Washington, and the US wanting to get out of Afghanistan and gather allies against China, India did not want to be in a position where, like in the 1990s, the US controlled the India-Pakistan narrative.

India will not reverse the abrogation of Article 370 or 35A. Pakistan’s campaign against this too has run its course. Kashmir will, therefore, remain off the table in the way Pakistan wants it. With local elections done, internet connectivity restored and a delimitation process underway, leading to state elections, India believes it can stand international scrutiny. Pakistan, India believes, is beginning to understand this. India believes Pakistan is also coming to understand the fact that India will take disproportionate military actions against terror. India wants a more peaceful periphery, because its primary interest currently is in controlling the Covid pandemic, getting its economic growth back on track and dealing with China.

India reckons that no matter what the solution in Afghanistan, it will lead to instability and cross-border movement of jihadis. This would not be in the interest of either India or Pakistan. An understanding on this could be attempted. Last, connectivity is a big part of India’s regional diplomacy. If Pakistan can work with India on connectivity to Afghanistan, and maybe Central Asia, it could be the beginning of a different chapter.

For the time being, India plans to stay quiet and let Pakistan’s government and army work things out among themselves. At this point, India will remain vigilant on the ceasefire and infiltration as another terror attack could upset everything. Since Pakistan had downgraded diplomatic ties, India will wait for Pakistan to restore them, which could see high commissioners return to their posts. There are other “sweetener” steps India is planning for Pakistan to help it change its course. They may not be what Pakistan wants, but they are all that India is willing to offer at this point.