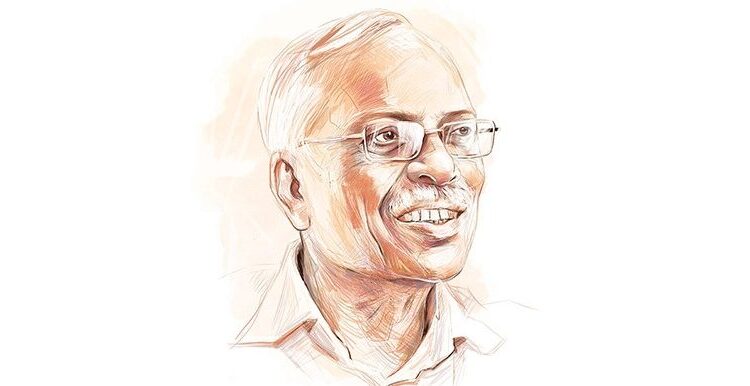

Mr Kutty From Karachi

In his own words Biyathhil Moideen Kutty left his home ‘in God’s own country’ Kerala & went to Pakistan. Mr. Kutty as he was widely known, was a Communist, a nonconformist. This is an incredible story of living with one’s political beliefs even while leaving own country & making a new country ‘home’. A Malayali settling in Pakistan with a lifelong love for Kerala. Uma Vishnu, a SAWM member, traces this journey of Mr. Kutty in Karachi and irrelevance of border as he passed away last month.

The summer of 1949. The subcontinent was still convulsing from the effects of a messy Partition — in India, Mahatma Gandhi had been assassinated the previous year and in Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had died, of tuberculosis, leaving the fledgling country rudderless. A few princely states, the Nizam of Hyderabad in India and the Khanate of Kalat in Balochistan, were refusing to accede to the respective dominions.

Some hundreds of kilometres from the border that now divided the two nations, a young mind was in tumult, too — friendless and homesick, weighed down by the guilt of his father’s expectations, the 19-year-old decided he had to get away from it all.

So in June that year, when the Government Mohammedan College in Madras shut for the summer break, the teenager didn’t go home to his family in Chilavil-Ponmundom, a village in present-day Malappuram district of Kerala. Instead, on a whim, he took the train to Bombay and, accompanied by someone he met there, left for Jodhpur and from there to Munabao, the last point on the Indian side.

From Munabao, he walked to Khokhrapar on the Pakistani side, along with the scores of men, women and children heading for the border. But unlike them, he was no muhajir or refugee of Partition, just confused — or was he curious? — possessing little more than the raw courage teenagers are endowed with. With no passports needed then, Kutty exchanged the few Indian currency notes he had for Pakistani ones (the same note, with “Government of Pakistan” stamped on “Government of India”) before boarding the train to Karachi.

That’s how Biyyathil Moideen Kutty reached Pakistan, his last name and lilting accent when he spoke Urdu arousing curiosity for the 70 years he remained a Pakistani citizen, during which time he plunged headlong into the country’s dizzying, unstable politics.

What began as casual meetings with the Malabar community in Karachi and beedi workers in the city turned into strident political activism, with Kutty emerging, by the 1960s and 1970s, as a key member of the National Awami Party (NAP) led by Mir Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo, a former governor of Balochistan and a liberal statesman of the socialist mould. Kutty, private secretary to Bizenjo while he was governor, remained his life-long associate. Yet, for “Kerala socialist Mr Kutty from Balochistan” — as Pakistan President Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto once introduced him to his compatriots — through all his years in Pakistan, what stayed with him was his unusual identity.

“People ask me even today why I came to Pakistan, leaving behind God’s own country, Kerala!” wrote Kutty in his 2010 autobiography titled Sixty Years in Self-Exile: No Regrets.

Kutty’s death on August 25 has revived these questions. What was a man from Kerala, free-thinking and liberal, with a strong Left influence, doing in Pakistan? And, despite his early brush with the politics of the Muslim League while in Kerala, how had he turned a communist in a country created by the Muslim League for Muslims?

Kutty was born on July 15, 1930, almost a decade after the Moplah Revolt of 1921, when the Muslim peasants of Malabar region, then a part of Madras Presidency in British India, rose in revolt against the oppression of the British and the feudal landlords. The revolt, which had been crushed with brute force, had left its scars on the region and its politics, with Jinnah’s All India Muslim League making inroads into the region. In his autobiography, Kutty says, “With a few exceptions, the Muslim students in our school, including myself, used to carry notebooks with Jinnah’s photos on the covers.” The period also marked the emergence of Left politics in Kerala, with the formation of the Communist Party in 1939.

But while Kutty was influenced by both the Kerala Students’ Federation (the forerunner of the present-day Students’ Federation of India, the CPI-M’s youth wing) and the Muslim Students’ Federation (the League’s student body) in his school and college days, there is little to suggest that it was politics or ideology that prompted his move to Pakistan.

Back at his ancestral home in Kerala, it would be a while before the family heard from him, recalls Muhammad Kutty, the youngest of the 10 Kutty siblings. “Before he went to Bombay, he had sent our father a telegram saying he would come home. So, for a few days, until we got another telegram saying my brother was in Bombay, my father would go to Tirur railway station around the time the train from Madras pulled in, and come back disappointed,” he says.

Their father BK Alavi, a north Malabar farmer, unlike the largely illiterate Muslim peasantry, had learned to read and write Malayalam and was insistent his children got an education for themselves, says Muhammad, speaking from the family home near Kottakal in Malappuram district.

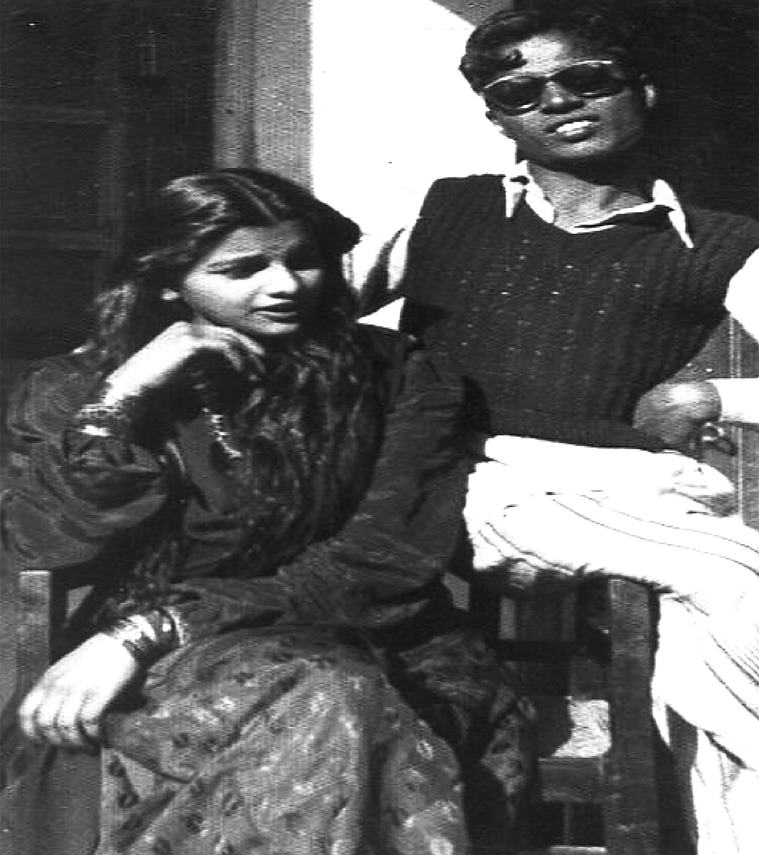

Kutty’s early years in Pakistan are a window into a country that’s barely recognisable in the present-day din of hypernationalism and jingoism on both sides of the border — the restaurants, dosa joints and paan and tea shops in Karachi run by pre-Partition migrants from Kerala; the foreign companies in Karachi and Lahore where the English-speaking Kutty was lucky to find jobs in senior positions despite his known political activism; and the English-speaking secretaries at these offices. Kutty eventually married Birjis Siddiqui, whom he fell in love with after spotting her through a peep-hole at his senior colleague’s home in Lahore and with whom he spent an eventful 59 years until her death in 2010.

But it’s the story of Pritam Lal, among Kutty’s earliest friends in Lahore and with whom he occasionally visited the “gorgeous” Lebanese dancer Angela’s cabaret in Lahore’s Marina Restaurant, that make this a story of simpler times — when identities and borders were less sharp.

Pritam lal was born Iftikhar Ahmed in Indore in pre-Partition India but went to Lahore jilted, after his lover moved to Bombay. There, as he started working with a Hindu businessman, he took on his lover’s name (Pritam) to which he added “Lal”. But in the blood-baying years after Partition, he “converted” and became Iftikhar again.

Pakistan, meanwhile, vaulted from one crisis to another — rising tensions on the border with India, the assassination of the country’s first prime minister Liaquat Ali, rising nationalism in Balochistan and simmering discontent in East Pakistan over the West’s dominance, and, in stark contrast to India’s avowed non-alignment, an increased dependence on the West. It was a position that made the country’s rulers deeply suspicious of the Soviet Union, and, by extension, the communists in their midst, eventually leading to a ban in 1954 on the Communist Party of Pakistan.

Kutty, who had by then had a series of encounters and meetings with the progressives and communists of Lahore and Karachi, among them a few Sunday meetings with the literary giant Saadat Hasan Manto at his flat in Lahore, had found his own politics. He mobilised the beedi workers of Karachi, almost all of them pre-Partition migrants from Malabar, to set up the Kerala Awami League as a wing of the Karachi chapter of the Awami League. With the US dominating Pakistan’s foreign policy through almost all its years of existence, Kutty’s politics of socialism and strident anti-imperialism meant that he was always in the opposite camp.

Later, Kutty was to join the Pakistan National Party, which, with the merger of the Bhashani faction of the Awami League in 1957, became the National Awami Party (NAP) — a party that took on Pakistan’s military regimes and, after the 1971 war, became the principal Opposition party to the Pakistan People’s Party led by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

Kutty’s politics were to land him in prison on more than one occasion. The first of these was during the dictatorship of Mohammad Ayub Khan, with Pakistan under martial law. Though Kutty never held any top political position, his close association with the progressives and the anti-establishment parties, besides his unusual surname and his frequent visits to India and Kerala, were to place him under surveillance, says VP Ramaachandran, former editor of the Malayalam daily Mathrubhumi. “Those days, I was a correspondent for (news agency) UNI and our office in Lahore was across the road from Burhan Engineering Co Ltd, where Kutty used to work. After I got my wife to Lahore, our two families became very good friends,” he says.

It was an association that deepened the suspicion about Kutty being an “Indian spy”. He was jailed for 28 months, from October 1959 to August 1961, during Ayub Khan’s regime. One of the things the police officer interrogating him showed was a casual photo of the Kutty and Ramachandran families — their wives and children — while in Lahore.

His jail stints earned him respect and friendships such as that of Raza Kazim, a Marxist, an accomplished lawyer and a businessman who turned the rules of entrepreneurship on its head by employing socialist practices in his shrimp business, where Kutty was employed for a while. “He had a character of steel. The purpose for which he came to Pakistan from Kerala was fulfilled — he wanted to work here and change the society for the better. He had a heart of gold,” says Kazim, now 90 and living in Lahore.

It was while in NAP that Kutty met Bezenjo, a communist leader in pre-Partition India who had quit the party to join the Baloch nationalism movement. After the NAP and its junior partner Jamaitul Ulemai Islam (JUI) won a majority in Balochistan and North West Frontier Province (now Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa) in the 1970 elections, Bijenzo became governor.

“After my father’s death, all the training in communism that I received was from Kutty saab,” says Mir Hasil Khan Bizenjo, Bizenjo’s younger son who is now president of the National Party of Pakistan that has a presence in Balochistan. “My father relied heavily on Kutty saab. He had excellent drafting skills — he drafted all the party’s manifestoes, etc. He was governor of Balochistan and Kutty his political secretary,” says Bizenjo Jr. But the provincial NAP government barely lasted nine months, with Bhutto dismissing it. “Among the first political activists to be arrested by the Bhutto government was Kutty saab. Later, my father, too, was jailed in the Hyderabad conspiracy case, in which Opposition leaders were tried for treason,” he says.

Despite their sharp differences, Kutty had several interactions with Bhutto while he was president and later prime minister. In 1973, with Kutty in jail in the Hyderabad conspiracy case, his daughter Yasmeen, a student of Bolan Medical College in Quetta, was stopped from attending classes. Angry that the government was targeting his family, he shot off two letters to Bhutto, after which Yasmeen was granted admission in Lahore. Bhutto often relied on Kutty in his attempt to buy peace with Bizenjo, who once mildly chided him for being Bhutto’s “errand boy”.

All through Kutty’s political activism and his arrests, it was his wife Birjis, daughter of a family from Amroha, who kept the family together. Kutty, in his book, writes of her hardscrabble life with him, “…imagine, Birjis was a girl who had so many wooers in her elite family itself that she could have easily got herself married to one of them and lived happily ever after!” “There was a time when my father was in and out of jails. But never did my mother complain or make us feel inadequate about it. She was his steady support… She would even make kebabs to supply to my walid (father) and his associates in jail,” says Jawaid Mohyuddin, 66, the eldest of Kutty’s three children, who studied engineering at Lumumba University in Moscow at a time when Pakistan was deeply suspicious of the Soviet Union.

Jawaid, who retired as project director at water and power development authority in Karachi, now lives with his wife and four children in the city’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal area. It was here, a floor above Jawaid’s, that Kutty lived till his last days with his youngest daughter Shazia.

In his later years, Kutty devoted himself to the cause of peace between the two neighbours. Among the founders of the Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy, and, later, the Pakistan Peace Coalition to lobby against nuclearisation in the subcontinent, he led several initiatives that frequently brought him to India, where he established relationships with Gandhians such as Nirmala Deshpande.

Despite his connections with home and his frequent visits to India and Kerala, Kutty remained a “true Pakistani”, says VN Asokan, former editor of Mathrubhumi, who met Kutty when he went to cover the Saarc summit in Islamabad in 1989 and kept in touch. “He sincerely wanted India-Pakistan relations to improve. There is unlikely to be another flagbearer for India-Pakistan peace like him. Both the countries used him for Track 2 diplomacy. But, at heart, he was a true Pakistani. He would always take Pakistan’s side during discussions and debates,” says Asokan.

Karamat Ali, executive director at the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER), however, disagrees. “Kutty rejected narrow nationalism and so I don’t think that he took any side. He was a communist and a true internationalist. In case of India and Pakistan, his position and thinking were always wider and he looked at it in the South Asian context. He always talked about peace and dreamed about prosperity of the region,” he says. Kutty spent the latter part of his years at PILER, an institute that mobilises workers around issues of labour rights.

Congress leader Mani Shankar Aiyar, former diplomat and India’s first consul-general in Karachi between 1978-82, says Kutty carried a “Malayali ethos into Pakistan”. “He had very liberal ideas of socialism and secularism. There was nothing anti-Pakistan about what he said, but his concept of what it meant to be pro-Pakistan was to be pro-India because he thought it was in the interest of both countries to be friendly with each other,” says Aiyar, who first met Kutty in 1979-80.

So could Kutty have crossed the border today? Would a Malayali have settled into Pakistan with the ease with which Kutty did all those years ago? Ali of PILER says, “A lot of people from Kerala had come to Karachi, then part of united India, during the 1921 Moplah Rebellion and the Khilafat movement. These people were known as Malabari, not Malayali, and since they had fought the English, there was a lot of sympathy for them. Besides, they were quiet and peaceful. They opened tea shops and other small businesses and got integrated. So, when Kutty came in 1949, there was already a good number of people from Malabar. He was a very conscious political soul, given his association with student bodies in Kerala and he made a decision to come here — it was no accident. Given this background and the attitude of the people of this part of the world, I don’t think there would have been any difference had he come today. The only difference could have been that of Pakistan-India relations, which, unfortunately remained strained since Independence.”

Yet, nothing, neither borders nor dictatorships, tempered his love for Kerala. “He never gave up Kerala. At home in the evenings, he would always be in his lungi. Kerala food was always his first choice. When he used to eat at PILER’s canteen, he always added green chilies to his food and asked for additional salt,” recalls Ali.

The rains reminded him of a home he left long ago. Says Jawaid, “Even in his last years, after paralysis largely confined him to our home in Karachi, he would look out of the window and talk of how it reminded him of Kerala.”