Normalising the Death of a Free Press

This story first appeared in The Wire

A good chunk of the media is sold out to the establishment while the rest of us seem to have internalised the need to discipline our minds by not offending the power holders because the consequences are fearful to contemplate.

Now that the brouhaha and the noise of the G20 have slowly, but surely, subsided and the applause has ended, it’s time to get down to business, but not in the usual way.

Even while the G20 conclave was ongoing and all media attention was focused on the dignitaries and their excessive displays of affection, Manipur had not ceased to exist. However, its tyrannical distance ensured that it received no attention from the visiting heads of the new ‘Global South’, a term that only geopolitical experts and diplomats can play around with.

To the ordinary Indian these impressive-sounding words are not going to make a dent in their lives. Those at the bottom of the economic ladder live with the bare minimum salaries and have no assurance of where the next meal will come from. This is what’s happening in the relief camps of Manipur, particularly in the hills where rations and essentials through the formal government route have not been arriving as they should.

And look at the media! Did a single one of us ask the prime minister, who otherwise visits the region he calls “Astha Lakshmi” several times during the election season, why he doesn’t care to visit a state in deep turmoil and ruled by his party?

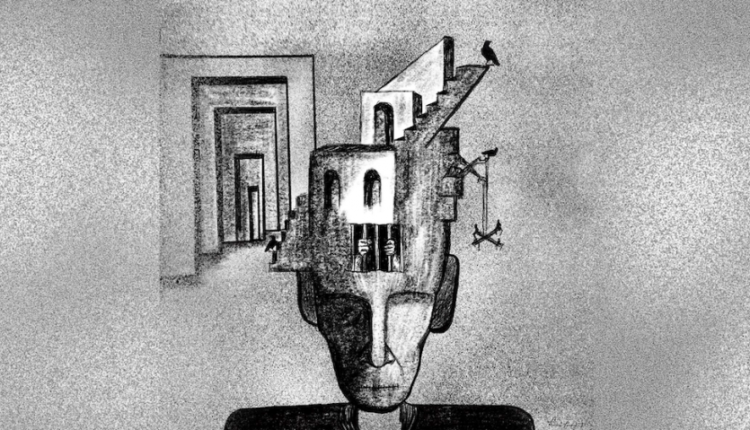

It is strange that the media has no access at all to the prime minister of the so-called “Mother of Democracy”. It is true that a good chunk of the media is sold out to the establishment while the rest of us seem to have internalised the need to discipline our minds by not offending the power holders because the consequences are fearful to contemplate. But how did we arrive at this juncture and where is the spirit to fight the demons that are chipping away at the democratic pillars?

Manipur’s media coverage

Let’s turn our attention to Manipur and the media coverage from the troubled state. One thing is clear: the mental, emotional, social, and political divide between the tribes, occupying the hills of Manipur and those in the Imphal valley, is complete.

People from the region who flit in and out of these seven states for varying reasons have a better idea of the cultural and ethnic sensitivities as compared to the journalists flying into Manipur from the outside, with tight deadlines to meet.

It also depends who the journalists speak to and whether they have figured out that at this juncture, there is no such thing as a ‘sane’ voice that can give them a non-partisan, objective account of things as they play out on the ground. Talk to one group and it’s their account; talk to the other and it’s their carefully curated narrative.

How can a journalist, without any training in conflict reporting, operate in a region that has never really been psychologically and emotionally integrated with India?

Besides, who really waits for the traditional/legacy media these days? People avariciously consume social media and YouTubers, most of whom present their narratives, often without mediation or language moderation. Reading the news that is edited in New Delhi or elsewhere feels bland to those that have learnt to rely on instant news.

There’s another section of the media that has been told by their editors what to look for and why. In these polarised times, the media has taken a big hit but journalists don’t seem to have the moral courage to fight back.

Several instances of discrimination, but no questions

The ongoing Internet ban is not uniformly applied and seems to favour one group against another. To meet their deadlines, reporters had to go to the IPR office in the Imphal valley to send their news across. This would mean that Imphal still had a semblance of internet connectivity; the hills were completely cut off.

In Manipur, both groups have learnt to control the narratives and project themselves as victims. The reality is that the hill tribes are more badly affected due to logistical disadvantages. They also have no outlet outside Manipur, except through Mizoram, which requires a lengthy drive on what is often referred to as ‘offroad’ terrain.

A noted singer and lyricist, Mangboi Lhumdin, who also was a village volunteer along with four others, died as a result of a bomb attack. Lhumding was taken to Mizoram for treatment but died on the way.

The video of the two Kuki-Zo women paraded naked shook the conscience of this country and the world, but even that was short-lived.

No G20 member wanted to ask any questions on that horrific video. They were probably all bamboozled to ask only diplomatically correct questions.

Recently, the discrimination meted out to tribal students by the Manipur University was out in the open. Out of 76 students studying Psychology in Rayburn College, Churachandpur, only 10 students passed. After the Indigenous Tribal Leaders’ Forum (ITLF) complained to the Vice Chancellor, the results were reviewed and drastically changed within two to three hours. The number of passed students went up from 10 to 41.

The ITLF has asked the University Grants Commission to carry out a comprehensive audit of the results and transfer the tribal students to other reputed state universities. It is evident now that the Kuki-Zo people (students, office-goers, university employees, etc.) will not be able to return to their jobs/university/businesses in the valley.

This brings us to the next question. Will the Imphal valley – which has been a hub of diversity for as long as we can remember – become an exclusive home of the Meteis? Is diversity going to be lost forever? How do people of the same state be divided by barricades and bunkers where each side sees the other as the enemy? Who is going to be the first to smoke the peace pipe?

For now the Nagas are waiting and watching the developments. There is no knowing what the Naga reaction will be if the Kuki-Zo people dig in their heels on the separate administration issue.

The media has forgotten to remind our audience of the torture meted out to chief minister N. Biren Singh’s adviser, a Bharatiya Janata Party Kuki MLA, Vungzagin Valte, who is partially paralysed, per reports. But by far we failed in our journalistic ethics when we reported what Tushar Mehta, the Solicitor General (SG), told the Supreme Court. He said the bodies lying unclaimed in the morgues are those of infiltrators.

How did the SG establish the identity of the dead? Should the media not have questioned that report?

Clearly the media has a lot to answer. Although some sections of the media have provided analytical coverage, offering readers insight into the evolving situation in a conflict-ridden state, which is in a civil war-like situation, where people are caught in the binaries of oppressor and oppressed.

Having spoken with friends from both the hills and the valley, coupled with the facts available, it appears that only a section of extremists from both sides is responsible for waging a conflict that has inflicted immense suffering on thousands.

Writing about the “cultural miasma of fear and exhaustion” in North America, Peter Stockland of the think tank Cardus says this is “producing a cynicism so deep and murky and toxic that it verges on the sin of bearing false witness against reality.”

I believe this is what has happened to the best minds both in the hills and in the valley.