The Demolition of the National Museum Will Extinguish the Identity of an India That was Born in 1947

This story first appeared in The Wire

There seems to be no logic behind breaking down the present structure and shifting the nearly two lakh artefacts to North and South Blocks.

It was a new museum in New Delhi for a new nation, born in 1947. The National Museum grew out of an exhibition that travelled to London in 1948 and then came back to a temporary location within the Rashtrapati Bhavan on Raisina Hill.

The new National Museum was built by new India as “ways and processes through which modern identities and associated cultural practices are contested, challenged, and (re)configured),” Tapati Guha Thakurta, distinguished historian of art and art institutions wrote in Monuments, Objects, Histories – Institutions of Art in Colonial and Post Colonial India.

The ways and processes were unexpected, as Saloni Mathur and Kavita Singh have pointed out in their book, No Touching, No Spitting, No Praying because of the “notorious unwillingness on the part of India’s subaltern masses to follow the museum’s cultural script” by transforming the event of the visit into an entertainment as well as a darsan, a dialogue between the innumerable deities on display and the devotee.

Museums in India are identified by the “subaltern masses” as places of wonder or magic, the Ajaib Ghar made famous in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim or the immensely popular tourist destination of the masses, the Jadu Ghar or Indian Museum, where thousands visit en route to the pilgrimage at Ganga Sagar in the Sundarban or political rallies in Kolkata.

The incomplete complex – the final part was to be constructed in 2017 – that is the National Museum today on the intersection of erstwhile Rajpath-Janpath roads is waiting to be demolished as the plan for the central vista includes its erasure. Why a building, one part of which was completed in 1960 and the second part in 1989 needs to be destroyed is unclear. The venerable Indian Museum building in Kolkata was constructed and opened in 1878. It is the ninth oldest museum in the world and Asia’s first museum. The British Museum building was completed in 1852.

The reported demolition and the plan to make a museum out of North and South Blocks – purpose built offices for the imperial Government of India and after 1947, of the new republic – by March 2025 is bizarre. There is no logic to the upheaval; a purpose built museum will be demolished and two purpose built offices – North and South will be emptied to become the Yuge Yugeen Bharat Indian Museum. Buildings have histories and demolition is a brutal erasure that rashly overwrites the past.

As Thakurta asked “what is the announced reason behind the demolition of the 1960 building of the National Museum and the placing at immense risk of all the irreplaceable archaeological and art historical artefacts that it houses? It is a public institution, always intended to be one, and every government stands obliged to hold these objects in safe and professional custody for the nation and for posterity.”

The reported timeline is irresponsible. The National Museum has two lakh artefacts, most of which are priceless and a part of not only India’s heritage and identity but world heritage too. Anyone who has ever moved a modest household could tell the Ministry of Culture the impossibility of vacating a premises with two lakh objects within weeks, because the deadline to empty out the existing National Museum buildings has been set for the end of the year. It took the British Museum two years to declutter, revamp and refurbish the Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery of China and South Asia with its 2000 objects housed in a 115 meters long gallery, because such displacements pose serious curatorial challenges.

Former Culture Secretary Jawhar Sircar has been asking for details ever since the central vista plan was unveiled. He said “I have received only evasive replies,” to questions on if a tender has been called to find a firm that will handle the packing and storage of the two lakh objects? Common sense suggests that invaluable artefacts cannot be simply packed and shoved into storage. Specialists, of all the different categories of artefacts in the National Museum’s collection, have to be identified and vetted and then allowed to do the job.

National Museum’s priceless artefacts cannot be put into just any warehouse or even a storage complex. Such artefacts need maximum security to ensure that what goes in can be retrieved intact and authentic. Across the world, there are secretive, super secure, special buildings that house priceless artefacts and art works in transit from auction houses, private sales and to their final destinations. Most of these storages, like the Headquarters building in Geneva Free Port, are large windowless concrete blocks surrounded by barbed-wire fences, designed to resist earthquakes and fires. Such buildings on the inside have several rooms that follow specific criteria to fit the highest conservation conditions. Artworks and antiquities are stored in moisture and temperature-controlled rooms conceived as impenetrable safes. They are locked behind nameless, armoured doors built to hold out against explosives and equipped with biometric readers granting access to only the legally authorised few.

The absence of details and unsatisfactory replies to Sircar suggest that the entire business of packing up and storing the National Museum is opaque. Sircar said that he had been pursuing the matter and every time he felt he was being fobbed off with replies like “no firm decision has been taken.”

Museums in India loan artefacts for exhibitions in different parts of the country and overseas. These are small bundles of objects for which there are obviously specialists who can handle the packing and shipping. But packing up two lakh artefacts is an entirely different business. The storage is equally problematic. In the context of the National Museum, as Singh had pointed out in the lecture series ‘Modern Art for a New Nation’ curated by Thakurta, many of its best objects are loans from museums as distant as the British Museum in London, the Patna Museum, the Chennai Museum and the Indian Museum in Kolkata.

As national treasures, the safekeeping of which has been given to the officials of the National Museum and the Ministry of Culture and therefore by extension to the government headed by Narendra Modi, India’s citizens have a right to be informed, in detail and with transparency, how this near impossible task will be executed. Thakurta questioned “Does this government have any legal right to meddle with institutions like the National Museum and the National Archives and endanger the historical inheritance of the people of India?”

Demolishing the National Museum because it is aged and infirm, even though it is a mere 60 years old is one thing. Housing it in the North and South Blocks, which are even older and considered unsafe, because they are not earthquake proof seems incredibly silly. More so, because as Sircar pointed out museums need enormously strong load bearing walls, because a lot of the artefacts are very heavy indeed.

The decision is irrational. Thakurta’s dismay is evident: “What is terrifying is the Ministry of Culture’s complete silence, evasiveness and lack of any clarity about why the current complex must be demolished and moved to completely unsuitable locations like the office buildings of the North and South Block.”

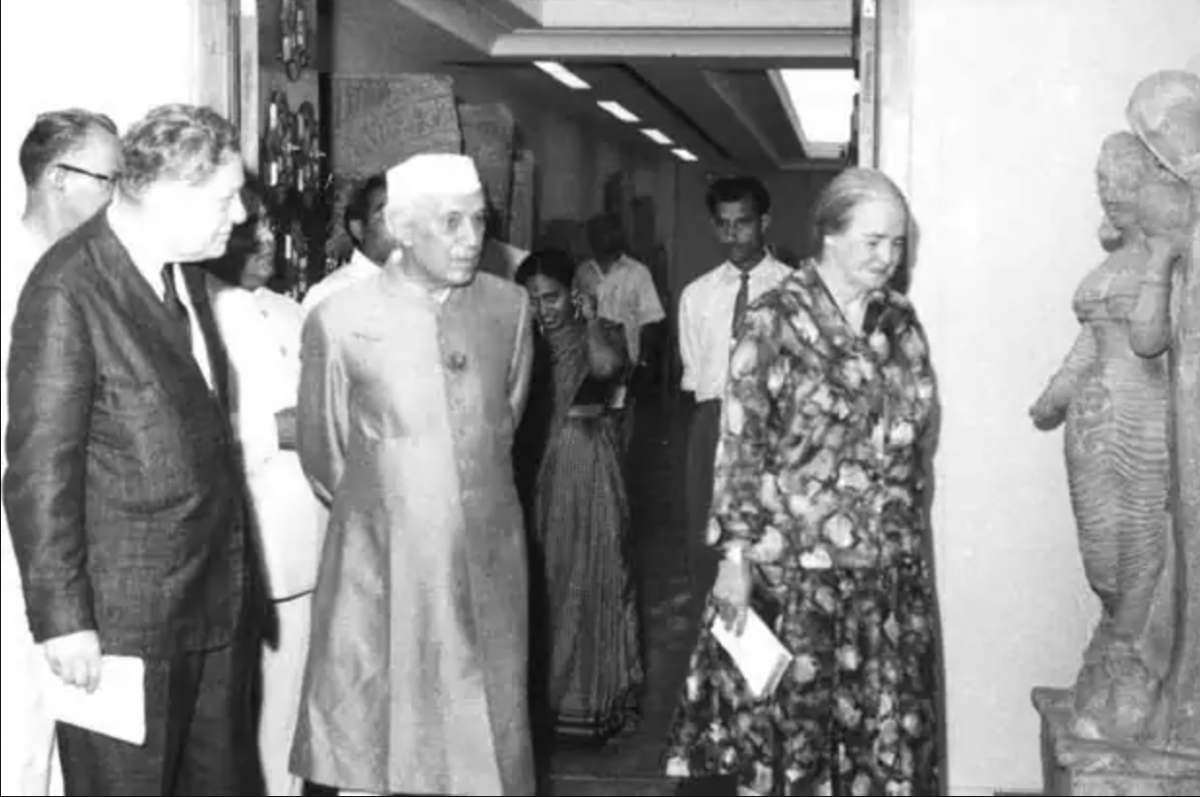

The original design for the National Museum was for a complex with three parts. The first was the main building inaugurated by Jawaharlal Nehru, the second was opened in 1989. The foundation stone for the third part was laid on December 18, 2017. The National Museum “is also already part of a well-conceived cultural complex that was conceived by the builders of New Delhi to sit at the heart of the Rajpath-Janpath artery of the capital” Thakurta says.

Grace Morley, the National Museum’s first director, took four years to decide which objects would be displayed and how. She was invited by the government of Jawaharlal Nehru to do this, having worked as the director of the San Francisco Museum of Art before she came to India. As an advocate of cultural democracy she ensured that the display design of the National Museum reflects “secularisation and democratisation” in the presentation of sculptures in white cube spaces with minimal contextual information.

There was a very good reason for the way the National Museum displayed its collection. It was to “celebrate the ancient culture of a young state ” as Singh wrote in The Idea of a National Museum. It was “an act of great symbolic importance.” It was within this structure that India believed it could “share its masterpieces with its citizens in a symbolic affirmation of their rights.” It also narrated through the materiality of stone, particularly sculpture, a nationalist history, according to Singh.

Tracing the connect between archaeology and the analytical framework Thakurta argued that “history was not always extracted from stone, rather stone became the proof of a preconceived historical cycle. The demolition of the National Museum building raises the question, is it the stone that offends a specific preconceived historical cycle?”

Museums in India have generally not been careful with priceless artefacts. The revamp of the Indian Museum caused breakages of the 2000-year-old Mauryan sculpture, the Yakshi guarding the doors to the Bharhut gallery. The 3rd century BC Lion Capital was damaged too.

The Museum in its present location in New Delhi is national. It belongs to the generations of visitors who spent time in it. The building, its location, its design and its artefacts on display tell the story of the nation as it was imagined at birth, inclusive, accessible and democratic. The deliberate dislocation cancels the story of version 1.0 of India when it was in its infancy.